“A kind of approach to nature”: Marc Chagall’s ceramic-making techniques

Sofiya Glukhova

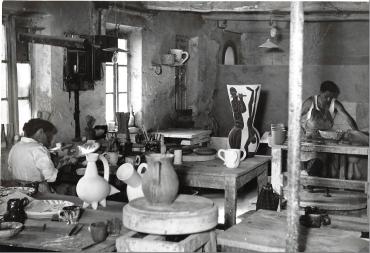

In his work with ceramics, which spanned 23 years from 1949 to 1972, Chagall seemed to focus fully on materials and techniques, continuously striving to push back their limits. He apprenticed with several local craftsmen1 before working mainly with the Madoura workshop while occasionally collaborating with Marius Giuge2 and Michel Muraour3. The artist was interested in every step of the production process. Each material and method offered him its own means of expression, contributing to each piece’s unique melody.

In Chagall’s hands, clay was much more than an inert material that he shaped, cut up, engraved and covered with velvety, glistening slips. With its grain, color and texture, it was a player in its own right, carefully attuned to each piece’s theme and spirit. The variety of local soils allowed him to fulfil his passion for rich materials. Chagall obtained various kinds of clay from the Société des Terres Réfractaires “L’Union”4 in Vallauris, the main supplier to the town’s ceramists.5 The rich, elastic, malleable, refractory and remarkably fire-resistant clays used to make cookware and decorative pottery in Vallauris and the surrounding area are sometimes grouped together under the general name Terre des Alpes6. The deposits are spread out in four localities bounded by the towns of Vallauris, Mougins, Valbonne and Biot7: Les Clausonnes, La Bouillide, Le Carton and La Colle. Ceramist and chemist Louis Franchet identified four types of clay8 that potters mixed together and that have been identified in Chagall’s work. The first is a yellowish, sometimes pinkish variety locally known as terre à feu (“fire clay”). The second, a thin clay containing grains of limestone, is called terre pour mélange (“mixing clay”) because it is never used alone. The third is a grey, highly plastic, white-firing clay known as terre blanche. The fourth is a red clay almost exclusively from Clausonne.

From the outset, Chagall used mixtures based on the terre à feu variety, firing them in warm, soft hues ranging from yellow ochre to several shades of pink. It can be seen in several pieces in the “Fables of La Fontaine” series, on the reverse side of plates or in the engraved lines, as in La Fontaine's Fables: The Two Bulls and the Frog [Fables de La Fontaine : Les Deux Taureaux et une Grenouille] (1950). The pale pink-ochre shade produces a soft glow in Biblical-themed plates, such as David and Saul [David et Saül] (1950), The Benediction or Isaac Blessing Jacob [La Bénédiction ou Isaac bénit Jacob] (1950) and Moses at the Spring [Moïse à la source] (1950), all from 1950. In the 1950s, Chagall also used terre blanche clay for dishes such as Two Women [Deux femmes] (1953)), shaped pieces (The Rooster [Le Coq] (circa 1951)) and tiles of varying sizes (Rooster or Lovers in the Rooster [Le Coq ou Amoureux dans le coq] (1961), The Pont-Neuf or The Couple or The Betrothed of Paris [Le Pont-Neuf ou Le Couple ou Les Fiancés de Paris] (1950 - 1952)). Red clay lends a particular depth and consistency to solid dishes, such as Ochre Bouquet [Bouquet ocre] (1955), but above all to the many sculptural-looking shaped pieces, such as The Lovers and the Beast [Les Amoureux et la Bête] (1957), Promenade II [La Promenade II] (1961) and Woman with Tilted Head and Bird in Flight or Woman Vase [Femme à la tête penchée et l'oiseau en vol ou Femme vase] (1971). Serge Ramel, whose pottery shop was on Place du Peyra in Vence, introduced Chagall to working with grog clay.9 Doubtlessly enthralled by its texture’s visual and tactile appeal, Chagall used grog clay with ceramic pastes of different colors, creating plates and various shapes. The texture of white grog clay can, for instance, be perceived through the glaze in Woman on White Horse [La Femme sur le cheval blanc] (1952).

As he learned traditional Provençal pottery-making techniques, Chagall’s forms evolved, leading to the creation of increasingly sophisticated shaped pieces. The artist began his apprenticeship with ceramists who had the deepest local roots, such as Mme. Bonneau at Poterie des Remparts10 in Antibes, alongside whom he made his first ceramic in 1949, and Serge Ramel who, like him, was also a painter. Between 1949 and 1953, most of his output featured utilitarian forms borrowing from medieval sources: round plates, rectangular dishes with turned-up edges, quadrangular plaques and oblong vases.12

From 1951, Chagall spent more time at the Madoura studio13 in Vallauris, where he continued to hone his technical skills14 by working on the “sculpture-vases”15, accompanied by ceramist Suzanne Ramié.16 He began making pieces such as vases, jugs and bowls. One of his first three-dimensional works was Elijahs Chariot [Le Char d'Élie] (1951) − in 1951 − a turned and modelled piece attesting to his physical and semantic sensitivity to the material. The impetuous team pulling a soaring chariot of fire, shaped and cut into the mass, stands out from the whirling movement of the red ochre clay vase left uncovered.

From 1950, Chagall produced ceramic murals made up of one or more tiles (Rooster or Lovers in the Rooster [Le Coq ou Amoureux dans le coq] (1961)), attesting to his interest in integrating ceramics into architectural space. The Crossing of the Red Sea, Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Grâce, Plateau d'Assy [La Traversée de la mer Rouge, Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Grâce, le plateau d'Assy] (1956), a large, 90-tile ceramic mural made at the Madoura studio in 1956, was mounted in the baptistery of Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Grâce chapel in Assy in 1957.17 The artist's earliest monumental work, it echoed the first stained-glass windows being made for the same chapel and the models for Saint-Étienne Cathedral in Metz produced in 1958, foreshadowing many of his later large-scale projects.

To create his unprecedented shapes, Chagall increased and diversified his ceramic working processes, using the main forming techniques: hand-modelling, wheel-throwing and molding. The Madoura studio’s ceramists and artisans supported him in his various practices. In general, the pieces were turned by Jules Agard (1905-1986) and molded by Loris Cerulli18 (1906-1983). Afterwards, they may have been modelled and shaped by Chagall himself, and counter-molded by Cerulli. Variously-shaped dishes (Rooster in the Dark [Coq dans la nuit] (1950), Characters, Landscape, and Bouquet [Personnages, paysage et bouquet] (1955)) were often molded and sometimes hand-modelled. Vases and receptacles with more traditional round shapes were turned, such as David and Bathsheba With the Moon [David et Bethsabée à la lune] (1952), Heads, Rooster and Fish [Têtes, coq et poisson] (1952) and Matte White Vase [Vase blanc mat] (1956). Different processes could be combined to make shaped pieces, also known as “sculpture-vases”, with counter-molding often determining the final shape. Several of Chagall's preserved ceramic molds attest that he used this process to make many shaped pieces, including Peasant at a The Peasant at the Well [Le Paysan au puits I] (1952), The Chimera [La Chimère] (1954), The Rooster [Le Coq] (1954), The Blue Donkey [L'Âne bleu] (1954), The Lovers and the Beast [Les Amoureux et la Bête] (1957), The Betrothed or Two Women [Les Fiancés ou Deux femmes] (1962), Promenade I [La Promenade I] (1957) et Promenade II [La Promenade II] (1961) and Large Figures [Grands personnages] (1962). To modulate his pieces and liven up the surface, he used hand modelling, but also added and removed material with a knife, as in Sculpted Vase [Vase sculpté] (1952) and Vase With Hand [Vase à la main] (1953), where the material was removed to create a surprising form. He often drew upon his experience as a printmaker, using the potter's dry point to incise thin lines and vibrant motifs in the raw clay. Antique sgraffito19 was one of his favorite techniques.

The piece was turned, modelled, molded and dried before being fired: “Ceramics, kneaded earth, depends on capricious and jealous fire. It takes hold of the unfinished work, modifying the project, exalting or destroying it.”20 The temperature for firing the biscuit ranges from 980°C to 1,100°C. Firing is a challenge that causes anxiety and excitement in artists wanting to push back the established limits of craftsmanship. Experiments failing to take constraints into account can cause the piece to break during firing. Chagall wrote: “Ceramics is the alliance of earth and fire, nothing else. If you give fire something good, it will give you back a little, but if it's bad, everything breaks. There's nothing left, nothing to be done. The fire's judgement is merciless.”21 Chagall apparently wanted to experiment at home in his villa “Les Collines” in Vence. He asked Roland Brice,22 known mainly for his work with Fernand Léger, about obtaining an estimate for building a kiln.23 Given the small size of the studio in Vence, its basic layout and the lack of anyone with the proper training who could assist the artist, it is not certain that it was ever built.24

The artist carefully thought out the shape, decoration and colors of each piece well before its production. Preparatory sketches in pastel, charcoal and colored pencil on paper, or pen on tracing paper, are proof of this. The sketches allowed Chagall to express his wishes to the ceramists who assisted him and to create his own designs.25 In less than two years, Chagall learned a variety of ceramic techniques that enabled him to transpose his pictorial universe into volume, give “flesh” to his creatures and characters and make the most of the visual effects offered by the art of fire. Unlike Picasso, who produced multiple copies of his ceramics, Chagall made one-off pieces. However, he did make small series of three to four pieces, such as L'Âne bleu [L'Âne bleu] (1954), Le Paysan au puits IV [Le Paysan au puits IV] (1952) and Les Amoureux et la Bête (version terre crue) [Les Amoureux et la Bête (version terre crue)] (1957) while varying their visual qualities with a choice of different colors.

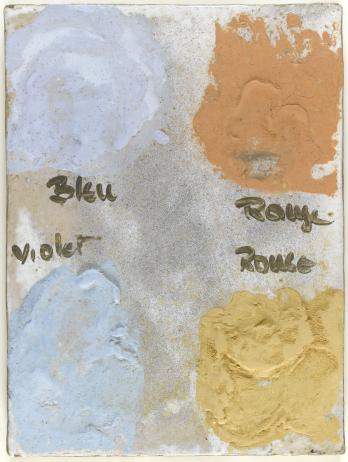

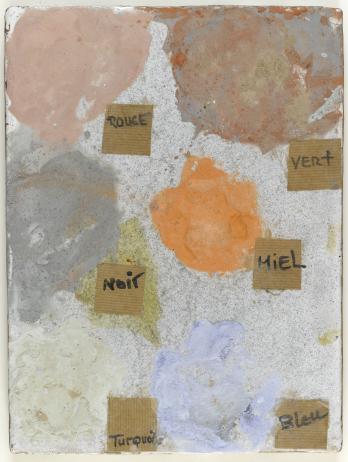

The ceramics were often biscuit-fired before the artist applied colored glazes and fired them a second or even a third time at between 950°C and 1,150°C. Slips – clay diluted in water – allowed the artist to vary the color effects or completely cover a piece before applying the glazes. A slip waterproofs the piece and refines its appearance, giving it a smoother, silkier look. Both uses of slips can be found in Chagall's work. Partial application allowed him to shade the clay’s natural hues, to leave matt areas in reserve, sometimes even next to the raw parts, and to combine them with the bright, shiny colors of metal-oxide glazes and enamels.26 As a painter, Chagall may have found it difficult to choose the glaze, as the colors of the oxides reveal themselves after firing.27 According to Alain Ramié28, one of the Madoura artisans’ roles was to tell the artists the exact color each oxide would turn. Chagall’s enjoyment of mixing led him to decorate some pieces with pastel colors. His clever combinations of volumes and shapes, textures and tints, colors and reflections made his ceramics unique, a quality recognized by masters of the art.29

Chagall placed great importance on technical skill combined with liberating inventiveness, but he rejected a purely decorative conception of ceramics. “My work in ceramics here in the South of France is a different experience, a kind of approach to nature, but one that avoids, if possible, extraneous decorative frills that, in my view, are worthy neither of the clay nor of the fire ceramics pass through.”30 Becoming a symbolic anchor after the dark and troubled times of the war, but also a link between past and present, clay seemed to offer Chagall a unique experience linking all humans and living things: “... the Earth imprints itself on us at the same time that it takes our imprints, our memory and our traces, the tangible remains of bodies that have disappeared, the bodies of all those who, born of the earth, have returned to it. This is what makes the Earth flesh, skin and the body of ancestors.”31 His relationship with the Earth, through ceramics, seems to have an existential dimension, as if he were striving towards a kind of union.

Access the search for ceramics in the online catalogue raisonné of Marc Chagall