The Mediterranean’s shores and sunny landscapes permeated Chagall's work after the Second World War. Settling in the south of France in 1949, he diversified his artistic practice, experimenting with ceramics and sculpture. Like Picasso, Chagall worked with the Madoura studio in Vallauris. His output included plates, dishes, serveware sets and vases, such as Heads, Rooster and Fish [Têtes, coq et poisson] (1952) and Matte White Vase (1956).

At the request of the publisher Tériade, who wanted him to illustrate Longus's pastoral Daphnis and Chloé1, Chagall traveled to Greece in 1952 and 1954, exploring Athens, Delphi and the island of Poros. "I'd wanted to see Greece for so long,"2 he said. These trips inspired the many preparatory gouaches for his Daphnis and Chloé lithographies, including Gouache for lithograph M. 330, Sacrifice to the Nymphs (Daphnis and Chloe, Longus) [Gouache pour la lithographie M. 330, Sacrifice aux nymphes (Daphnis et Chloé, Longus)] (1954 - 1956). It is not surprising that Chagall was interested in Greek ceramics. "I went to Delphi, the islands and Poros” he said. “I visited all the museums. The ones in Athens are magnificent. I contemplated the ancient paintings, the beautiful vases decorated with wild bulls on black and ochre backgrounds. What delightful wonders!"3

The black slip and ochre decoration of Heads, Rooster and Fish [Têtes, coq et poisson] (1952) evoke the ancient skills of craftsmen and painters of Greek red-figure vases such as the pelike attributed to the painter Aison by Beazley, which Chagall may have seen at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens4 (450-400 BCE, inv. 11485). Chagall’s incisions reveal his gesture and recall engraving, letting the clay’s color show through and creating lighter highlights. One side of this historiated vase features a rooster overlooking two figures facing each other, the man brushing the woman's face with his hand. The other side, which is simpler, shows a seascape with a crescent moon and a monumental fish. The rooster, also found on the Matte White Vase, symbolizes the artist's Jewish and Russian roots.5 A motif in Russian folk art and lubki,6 on this object it is alongside a fish, the symbol of Christ in paleo-Christian art, which can be seen in Fish [Le Poisson] (1952) and Daphnis and Chloe by Ravel: Final mockup for the backdrop of Act II [Daphnis et Chloé de Ravel : Maquette définitive pour le rideau de scène de l'acte II] (1958), attesting to Chagall's many sources of inspiration. He also made frequent use of symbols, hybridization and metamorphoses, such as Crowned Bird [L'Oiseau couronné] (1953) with its human face, that echo Greek mythology.

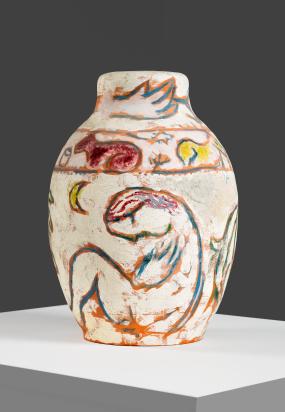

For his Matte White Vase, Chagall borrowed the decorative frieze motif7 from Greek ceramics in which zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures and plant motifs follow one another around the piece8. Combined with a light-colored slip and touches of red, these friezes, here featuring a three-part narrative unfolding on each side, could recall the wild goat-style Ionian oenochoes of the Orientalist period, such as the Levy Oenochoe (ca. 630 BCE) in the Louvre Museum. Chagall made the Matte White Vase at the Madoura studio based on a charcoal and pastel sketch (Sketch for “Matt White Vase” [Esquisse pour Vase blanc mat] (1956)). The velvety texture of the generously and briskly applied luminous slip might bring the fresco technique to mind. The material, in this case matte and vaporous, and its richness were extremely important to Chagall9, who enjoyed experimenting with different techniques. For example, he added sand, reminiscent of chamotte clay, to the canvas of his painting Mauve Nude [Nu mauve] (1967)10.

These two pieces are the work of Chagall the "Mediterranean".11 Like Picasso, he drew on Greek antiquity while departing from it and added his own personal references to create singular pieces that reveal his mastery of ceramics.

Ceramic

Matte White Vase

(Vase blanc mat)

- No. C-282

- 1956

- Vase

- pink ochre clay, decorated with oxides on white slips

- 12 3/16 in. (31 cm)

-

Signed Marc Chagall and dated 1956 underneath

- Pottery studio: Madoura

- Private collection

Related works

Marc CHAGALL, Esquisse pour Vase blanc mat (Esquisse pour Vase blanc mat), 1956, 13 3/8 x 10 5/8 in. (34 x 27 cm), Private collection © Fabrice GOUSSET/ADAGP, Paris, 2025

Marc CHAGALL, Sketch for “Matt White Vase” (Esquisse pour Vase blanc mat), 1956, 13 3/8 x 10 5/8 in. (34 x 27 cm), Private collection © Fabrice GOUSSET/ADAGP, Paris, 2025

Marc CHAGALL, Heads, Rooster and Fish (Têtes, coq et poisson), 1952, red ochre clay, decorated with slips and oxides, engraved with a knife and dry point needle, partially enameled with brush, 14 15/16 in. (38 cm), Private collection © ADAGP, Paris, 2025