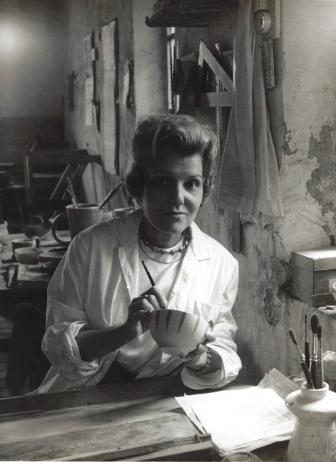

Suzanne Ramié, trial by fire

Ambre Gauthier

Suzanne Ramié (1905-1974), née Douly, began her training at the École des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, which she attended from 1922 to 1926, specializing in decorative motifs and ceramics. She worked as a textile designer in Lyon, notably for Gilet et Tahon, and at an advertising agency in Cannes owned by Aimé Maeght before moving to Vallauris in 19381. Vallauris was a major pottery-making center that had seen better days. Many workshops were abandoned2. Suzanne’s career as a ceramist began when she and her husband, Georges Ramié (1901-1976), took over a disaffected factory previously owned by the potters Foucard-Jourdan3. She learned the art of making enamels from ceramist Jean-Baptiste Chiapello (1888-1949), one of the oldest potters in Vallauris, while Georges specialized in firing the pieces4. The studio was called Madoura for the first letters in the words “Maison Douly Ramié”5 and began operating in 1938. In 1940, it was momentarily closed because of the war.6 Suzanne returned to Lyon for an exhibition of her first ceramics, which combined inspirations from traditional culinary pottery made in Provence with the beginnings of a freer, sparer technique that blossomed in Vallauris in the early 1950s. Her creations met with a favorable welcome from critics and the public on the Côte d’Azur in 1941 at the exhibition Artistes et Artisans à Cannes and in 1942 at the Arts et Traditions Populaires exhibition, where she won a gold medal.7

After returning to Vallauris, Suzanne played a key role in the postwar revival of pottery workshops, becoming the emblematic figure of ceramics in the South of France. Young potters took over other abandoned workshops, participating in the town’s revitalization and the creation of local ceramics, including Robert Picault, 8 Roger Capron, Jean Derval, Jean Rivier and the Tapis Vert studio9 headed by Claire and René Batigne from 1950. In the summer of 1946, Suzanne, André Baud and the potters of the Callis group held the first exhibition of Vallauris potters, “Poteries, Fleurs, Parfums”, in the lobby of the Nérolium.10 This is when Pablo Picasso met Suzanne Ramié.11 In 1947, they began an intense, lasting collaboration that resulted in 3,000 one-off pieces.12

Suzanne’s approach to ceramics was based on a personal reinterpretation of traditional forms of utilitarian pottery. Materials such as borage, gus, pichet and gourds came to life in her hands. Shapes became lighter and the decorative folk repertory gave way to their purity and raw strength. While Les Poteries françaises13 offered her a vast range of forms to explore, her penchant for sculptural shapes questioning the usual boundaries between ceramics and sculpture, and matte enamels and shiny monochromes, made her unique among all the other artisans in Vallauris. These reinvented architectural or volumetric forms gave rise to hybrid, biomorphic human figures and three-footed animals and found their quintessence in the Ring Vase (1956). With its archaic force and distant echoes of antiquity, this imaginary world redefined a Mediterranean modernity that ran counter to the styles developed by other workshops. Soon it was used and transformed by Picasso, who worked at Madoura on shapes designed by Suzanne. He had the exclusive rights to and was the only person to use them.14 Picasso fully incorporated Suzanne’s shapes into his work and contributed to the development of her repertory by opening up new formal horizons for her to explore, such as the ring forms of the 1950s.

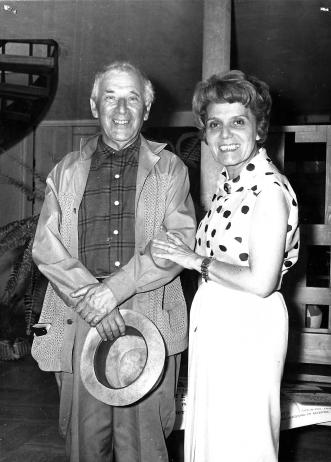

In the 1950s and 1960s, Suzanne faced the challenges of mastering ceramics techniques and worked with the greatest painters of the 20th century. The Madoura studio hosted Picasso, Chagall, Matisse, Brauner, Léonard Foujita, Baya and many other artists and ceramists. All of them beat a path to Vallauris not only to explore the relationship between earth and light and participate in the revival of the town's pottery workshops, but also for Suzanne's own artistic qualities. Her personal work, open-mindedness to age-old pottery traditions15 and eagerness to let artists use her studio and kiln allowed them to experiment with all the possibilities clay had to offer and give free rein to their self-expression. Suzanne’s ability to listen to, support and understand artists16 made her the personification of Vallaurian ceramics, nicknamed "Madoura" by Renée Moutard-Uldry in 1958.17

After trying his hand at ceramics in different local studios,18 Chagall began collaborating with Madoura in 1951. Attracted to Picasso's favorite part of France, he found a studio receptive to his own creations, yet completely taken over by Picasso's works. Chagall’s approach to ceramics differed considerably from the one developed since 1947 by Suzanne Ramié and Picasso, whose special relationship19 resulted in thousands of one-off pieces and multiple editions20. While these collaborations could be seen as rivalry,21 they were above all the expression of diametrically opposite artistic approaches and aesthetic worlds. Described as a "loner”22 at Madoura, with Picasso “monopolizing”23 the studio, Chagall usually went there when he was away24 and worked mainly with turner Jules Agard and decorator Yvan Oreggia for enamels and firing, taking little heed of their advice.25 He worked on existing forms or created his own, modeling some of them by hand, and rejected many of the smoother, more regular turned forms26 that Picasso preferred. Madoura’s laboratory spirit, as well as the addition of pastel and chalk after firing, made it possible to create complex one-off pieces with fantastic, hybrid shapes that defied the rules of firing and explored the material’s fragility. Few written traces of this collaboration have survived, although some letters between Chagall and the Ramiés describe how it worked.27 Nevertheless, it is certain that Chagall was fully aware of the quality and specificities of Suzanne's work, and that her sculptural approach and fine craftsmanship resonated with his own. Chagall's work at Madoura from 1952 to 197228 attests to his trust in and admiration for the techniques used in the studio. Only one of his ceramics comes close to Suzanne's personal creations: The Offering to the Lovers (1954) strongly recalls the ceramist’s slender-necked bottle vases from the early 1950s.

Madoura opened a gallery in Cannes in 1961 and in Vallauris in 1965, mainly to sell editions of Picasso's ceramics. They were exhibited in Paris galleries29 and at various Vallauris events. Gradually, Picasso's intense production took precedence over her personal creation. The first posthumous tribute was paid to her in 1975 with a major exhibition at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in her native Lyon, highlighting the refinement and modernity of her creations.30

Access the search for ceramics in the online catalogue raisonné of Marc Chagall