The “promised land of beauty”: ceramist painters and sculptors in southern France in the 1950s

Sofiya Glukhova

The interest of painters and sculptors in ceramics dates back to the 19th century and grew in reaction to industrialization under the influence of the Arts and Crafts movement founded by William Morris and John Ruskin’s reformist ideas. Breaking down the boundaries between the major and the minor arts, the phenomenon continued and grew throughout the 20th century, gradually spreading to European countries, including France. In 1886, Paul Gauguin took up ceramics at the Haviland brothers’ Auteuil studio headed by Ernest Chapelet, while André Metthey made glazed earthenware and stoneware pieces, inviting the famous Nabis and Fauvist artists to his studio in Asnières: Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis, André Derain, Kees van Dongen, Othon Friesz, Pierre Laprade, Henri Lebasque, Odilon Redon, Georges Rouault, Ker-Xavier Roussel, Louis Valtat, Maurice de Vlaminck and Édouard Vuillard. After the First World War, the avantgarde took up the art of fire—De Stijl, Russian Suprematism, the Bauhaus, Italian Futurism—putting objects at the heart of their reflections on politics and society.

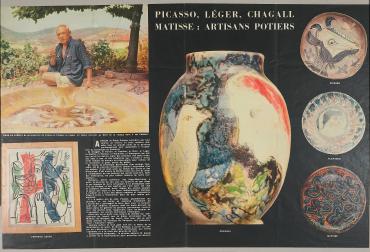

In the 1950s, the South of France saw the emergence of a new constellation of modern painters and sculptors, eager to dig their hands into clay and highlight the brilliance of enamel. They included Braque, Brauner, Chagall, Léger, Lurçat, Picasso, Pignon, Prinner, Ozenfant and many others. Artists pursued experiments underway since the early 20th century, marked in particular by “art from distant lands”1, but they seemed bolder and more prolific. After the Second World War, some artists set out to reveal the dialectical tensions between body and matter, past and present, near and far, private and public, that drove ceramic art during this period.

With its rich tradition of culinary pottery, Vallauris became a magnet for artists, although other towns were also known for their ceramics, including Antibes, Dieulefit, Biot and La Borne. This success is undoubtedly due to the presence of Pablo Picasso, who first visited the town in 1946. Vallauris was already known for its age-old ceramic workshops and its craftsmen’s skills, handed down from one generation to the next for centuries. After the Second World War, these craft villages revived their traditions and attracted many artists trained in art or applied arts schools, including André Baud, Roger Picault and Roger Capron and Georges and Suzanne Ramié, who founded the Madoura studio, where Picasso made his first pieces in 1947 before moving to Vallauris the following year. He soon became a fixture on the local cultural scene, inspiring and encouraging many artists to try their hand at ceramics. The Madoura and Tapis Vert workshops were the main venues. The Franco-American couple René and Claire Batigne, who founded the Tapis Vert studio, organized contemporary ceramics shows at Le Nérolium from 1949 to 1955, a period called the "golden age”2 of Vallauris. Lastly, the 1955 International Ceramics Festival in Cannes attracted 150 participants, attesting to the incredible vitality of ceramic art during this period.

After the Second World War, the attraction of painters to ceramics seemed to take on an anthropological dimension. Embracing the permanence of earth, they kneaded malleable matter. Shaping it between their fingers connected them to a universal gesture linking successive civilizations. Ceramics condense vitality in the face of primeval forces. Earth becomes the material that repairs and engenders new dreams: "Imagination and will, which at first might seem like diametrical opposites, are in fact closely intertwined ... In this way, the promise of beauty breathes life into energetically worked stiff materials and patiently kneaded pastes.”3

The summoning of archaic shapes and symbols spanning a vast timescale, notably through imagery recalling prehistoric art, the so-called primitive arts or even ancient cosmogonies, accompanied the return to the source material. Artigas and Miró worked not in the south of France but in Gallifa, Spain, near Barcelona. However, Miró visited the Le Plan studio at Madoura in 1947. His work was exhibited at Nérolium in 1952, attesting that he was as attracted to ceramics as other postwar artists. An interest in cave art, a heightened attention to the place of matter and the age-old magic of stoneware, flame and smoke deeply marked their abundant output.4 Victor Brauner continued to cultivate his interest in the occult, alchemy and astrology in pieces, mainly plates, dishes and pitchers supplied by the Madoura workshop. The exception is several, more boldly shaped anthropomorphic pieces, such as the Anthropomorphic Amphora, made on June 3, 1953. In an interview, Brauner alluded to the earliest artistic expressions: “We are in touch with the material. We repeat gestures dating back to the times when man first expressed himself.”5 Symmetrical figurative and abstract shapes and interlocking flat motifs in colorful compositions attest to his appreciation of the primitive arts, confirmed by his personal collection of African art.6 Brauner admired Hungarian-born artist Anton Prinner, seeing similarities with his own "old magical things”7 from the war years in his sculptures and terracotta works. In 1951, Prinner moved to the Tapis Vert workshops, where he broke free from the constraints imposed by his Paris studio, carving monumental figures from tree trunks, including the 4.2-meter-high Man (1956). After turning to clay as the primary material for his sculptures, Prinner also made ceramics, creating curious tableware, such as the esoteric Tarot service (1952). Other pieces are tinged with mysticism and oddness, such as the fabulous chess set The Sun Against the Moon (1951), evoking Egyptian divinities.

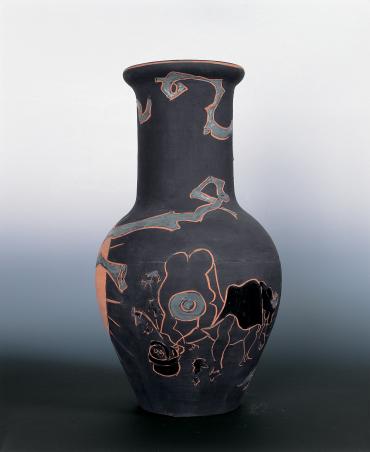

Another trend took shape: a certain regionalism that became a form of opposition to non-Western art. Picasso's Mediterranean roots are seen in pieces inspired by ancient Greek ceramics and mythology. “In Antibes,” Picasso said, “I returned to Antiquity8.” Ochre, red, black and white were used with a touch of irony on vases with ancient motifs, such as the series of large vases with nude women from 19509. Nymphs and fauns10 populate his creations, reincarnated in the earth that saw their “birth” centuries before. Édouard Pignon, originally from Pas-de-Calais, captured Provence through the motif of the region's emblematic olive tree, which he discovered in Sanary in the summer of 1948. He made watercolor on paper studies of its sinuous branches drenched in dazzling Southern light before being transposing them to ceramics. Figures of peasants plowing the fields highlight the link between man and the land, as they do in the Olive Pickers vase (circa 1953-1954).

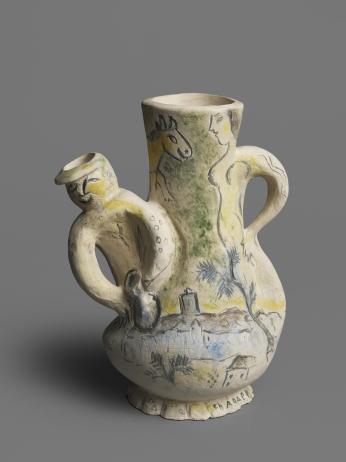

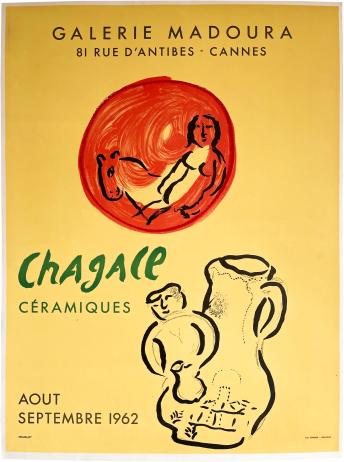

Back from years of exile in the United States, Chagall gradually settled in the South of France. In 1949, he began making his first ceramics, reflecting not only his constant curiosity about new techniques and a form of collective emulation, but also a heightened sensitivity to his environment. He made this adopted homeland his by enriching his pictorial vocabulary, introducing themes directly based on the surrounding landscape into his ceramics: the mystery of land and sea united under the sun (see Madonna with Tree [La Madone à l'arbre] (1951) ; Still Life With Fish [Nature morte au poisson] (1952)). But clay, color and light seem to be Chagall’s real means of putting down roots as he explored the contrasts between glossy and matte finishes, glazed and unglazed clay, light and shadow in his ceramics. The archaic technique of sgraffito, known in the Mediterranean basin since Antiquity, involves engraving lines or designs on the clay or the engobe. Chagall had mastered and abundantly used the method since his earliest engravings in the 1920s (see La Fontaine's Fables: The Fox and the Grapes [Fables de La Fontaine : Le Renard et les Raisins ] (1950), Double Face in Green [Double visage en vert] (1950) and Large Figures [Grands personnages] (1962)). Chagall saw a connection between the fertile land of the South and his homeland. "It suddenly seems to me that this light-colored earth calls out from afar to the dark earth of my native Vitebsk," he said in a 1950 interview with Georges Charensol11. He continued to evoke Russian folk art and his hometown, with its emblematic little homes, in ceramic pieces such as The Peasant at the Well [Le Paysan au puits I] (1952) and The House [La Maison] (1952).

The intimate experience of the material-memory that is ceramics evolved towards a desire for monumentality. Artists and sculptors sought to go beyond the medium to create more imposing ceramic sculptures: bas-reliefs and ronde-bosse in stoneware, ceramics and wall sculptures. The "temptation of the monumental" shifted ceramics from domestic to public and urban spaces, meeting the postwar need for reconstruction and transformation. Fernand Léger thought it was important to “treat the wall in the city, in architecture, in the landscape, outside and inside the home to bring color to life in large dimensions12”. The artist made his first bas-reliefs in Biot between 1949 and 1952 in collaboration with Roland and Claude Brice. He made monumental ceramics (for example, Women with Parrot in the garden of La Colombe d'Or, Saint-Paul) before receiving commissions for architecture, such as the ceramic and mosaic gable wall of the Alfortville gas plant and the velodrome in Hanover, which ended up on the main facade of the artist's museum in Biot.

With help from ceramist Michel Rivière, Édouard Pignon began his long series of monumental pieces in 1958, such as Man with a Flower, created for the Paris pavilion at the Brussels International Exhibition, before designing other large works in the 1970s. For Chagall, ceramics was a springboard to a wide range of architectural creations. In 1956, a monumental composition, The Crossing of the Red Sea, made up of 90 white clay tiles decorated with oxides and enamels, was installed in the Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Grâce church on the Plateau d'Assy, anticipating the painter's future mosaics and famous stained-glass windows. After the ravages of the Second World War, experimenting with ceramics gave many modern artists an opportunity to reconnect with the thread of history through a millennia-old, universal gesture on the Mediterranean’s sun-drenched clay shores, where this craft tradition has endured.

Access the search for ceramics in the online catalogue raisonné of Marc Chagall