From painting to ceramics: permeable techniques and cross influences following the “zigzags and curves of the mind”

Ambre Gauthier

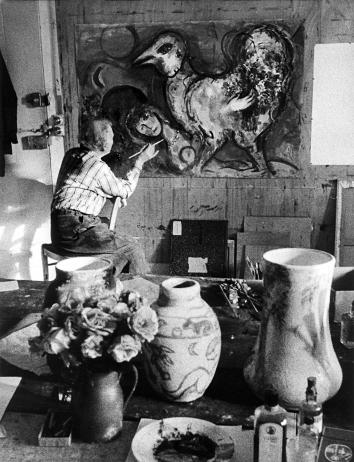

Chagall began working with ceramics in the South of France in the very early 1950s. This formative experience after his return from exile preceded his work in sculpture and stained glass, forming part of an interactive, multidisciplinary creative process in which all the techniques he explored interacted with, enhanced and complemented each other. Ceramics, which gave Chagall the opportunity to model and design two- and three-dimensional forms, bringing the characters and creatures in his paintings to life in space, cannot be seen as a distraction or a stand-alone technique with no relationship to painting. "Sculpture and ceramics are not entertainment, nor mere exercises to keep the painter in shape,” Jacques Thirion wrote. “They are the full blossoming of his art."1

Wishing to follow in the footsteps of the craftsmen in Vallauris, a pottery town, Chagall saw ceramics as a way to reconnect with time-honored craftsmanship and become one with the earth of the Midi, a physically and symbolically2 necessary step for him to renew his creativity. His first ceramics, exhibited at the Curt Valentin Gallery in 1952, "are a sort of foretaste: the result of my life in the South of France, where one feels so strongly the significance of this craft."3 As early as the first pieces produced in 1949, his ceramics revealed an interpenetration of experiments. Working with clay allowed Chagall to enhance his paintings and works on paper by experimenting with the intrinsic qualities of materials and firing techniques. Glazes inspired transparent effects, which appear in his drawings and paintings alongside his ceramic creations, as illustrated by Nude in Greece (1952).

The mother-of-pearl effects and pastel color ranges found in Large Figures [Grands personnages] (1962) were echoed later in The Memory of the Magic de la Flute (1976), attesting to the lasting imprint of ceramics on Chagall’s paintings. Later, his stained-glass work at the Simon-Marq studio in Reims explored the transparency and luminosity of materials, intrinsically linked to ceramics. Chagall also reintroduced lead lines and grisaille in his paintings,4 creating a geometric layout of space and strong contrasts (The Family [La famille] (1975 - 1976)

Moving back and forth between techniques, Chagall added Roussillon earth directly to works on paper, such as Daphnis and Chloe [Daphnis et Chloé] (1956), significantly extending his explorations of Vallauris’s red clay. This led to the creation of unglazed ceramics highlighting the material’s raw beauty, such as Elijahs Chariot [Le Char d'Élie] (1951). Materials were sometimes added to the paint. An example is Mauve Nude [Nu mauve] (1967), in which the addition of sand echos Chagall’s use of chamotte clay.5

The practice of modeling and ceramics was also a first step in Chagall's shift from two to three dimensions, paving the way for his first sculptures, dated 1951. Ceramics preceded sculpture in his experiments. Some (The Rooster [Le Coq] (1954)

Chagall's turn to ceramics was a necessary step in the renewal of his painting and the establishment of an evolving pictorial technique through the encounter with pure matter, its raw structure, its velvety texture and its light. Limited in time, these experiments attest that the search for plastic and pictorial matter was more important than subject or iconography: "The presence of fruit and flowers is also a visual matter ... graffiti can replace flowers.”8

These stylistic relationships, perceptible in the shift from one technique to another, reflect an artistic approach that saw one-off technical experiments as lasting contributions to the pictorial work, representative of "the zigzags and curves of [the] mind". Ceramics and sculpture were decisive stages of artistic experimentation and exploration for Chagall. They provided inexhaustible fertile ground for the artist, who never stopped building connections between techniques, playing with materials and effects to achieve creative synergy.

Access the search for ceramics in the online catalogue raisonné of Marc Chagall