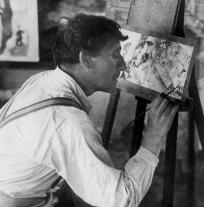

The artist’s studio is a recurring theme in art history—depicted in drawings, paintings, and photos. Looking at it through Romantic, 19th -century eyes, this fascinating place is the cradle of all artistic creation. At that time, artists were legendary, admired figures of society, and soon started setting trends1 for upper-class bourgeois and bohemians, who drew their inspiration from and fantasized about the lifestyle of the artist. Around the beginning of the 20th century, artists’ studios became an architectural model in Paris, inspiring new buildings with large glass roofs and high ceilings, bathed in light, boasting a profoundly “bohemian” interior decor—created by careful home-staging and a plethora of more of less luxurious items2. Later on, Chagall’s studio perpetuated this idea, fitting in perfectly with the collective imagination about his space. Photographs from the Marc and Ida Chagall Archive, as well as studio depictions, give us a glimpse of the atmosphere in these creative havens. Indeed, they took on many different facets depending on whether the painter was settled in Russia, France, Germany, or exiled in the United States during World War II. As it grew, Chagall’s studio morphed according to his social status and recognition as an artist—from his stay at La Ruche, a compound of studio lodgings in the Vaugirard neighborhood of Paris, from 1912 to 1914, to the construction of his villa La Colline in Saint-Paul-de-Vence where the artist settled down in 1966. These places were ideal for meeting new people and collaborating on cross-disciplinary artistic projects, transcending an extremely personal vision of the artist’s studio.

The works depicting his studio help shed light on what role and function the artist pinned on it. Chagall never painted outdoors: “I painted at my window, yet never walked down the street with my paintbox,” he asserted in Ma vie3. The artist’s studio is a pivotal place between outside and inside worlds, materialized by the window itself. In the same way as his self-portrait did, these studio representations bear witness to how Chagall considered his status as an artist—like a window into his world.

1Manuel Charpy, “Les ateliers d’artistes et leurs voisinages. Espaces et scènes urbaines des modes bourgeoises à Paris entre 1830-1914”, Histoire urbaine (“Artists’ Studios and their neighborhoods. Urban Areas and Scenes of Upper-Class Bourgeois in Paris between 1830 and 1914,” Urban History), vol. 26, no. 3, 2009, p. 43-68.

2Ibid.

3 Marc Chagall, Ma vie (My Life), Paris, republished by Stock, 1983, p. 166, in Élisabeth Pacoud-Rème, “Chagall, fenêtres sur l’œuvre” (Chagall, Window onto his Works), in Chagall, un peintre à la fenêtre (Chagall, a Painter at the Window) (Nice exhibition catalogue, Nice, Musée national Marc Chagall, June 25–October 13, 2008, Münster, Graphikmuseum Pablo Picasso Münster, November 13–March 4, 2009), Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 2008, p. 33.

The Death, the key work of Chagall’s youth, was displayed for the first time in 1910 alongside work by other students from the Zvantseva School in Saint Petersburg. The show, held by Apollon magazine (1909-1917), marked a turning point in the endorsement of new artistic research. This was much to the displeasure of upholders of academic art, who did not fail to express their hostility, including painter Ilya Répine1. The painting’s theme, which came to Chagall one day “in the sky […] fully composed2” uses codes from theatrical staging. The work contains characters who are both interdependent and opposing the same time, “each merely a word in a complex poetic phrase3,” and eludes any fixed symbolic interpretation. Beneath a sulfur-colored sky, a corpse lies surrounded by six church candles, lit as for a funeral. The black soil underneath him, to which he is about to return, connects the world of the living with that of the deceased. On the left-hand side, positioned high on the roof of a house as if removed from human tragedy, a man plays the violin, providing a musical accompaniment to the mysteries of the universe. A sobbing woman, her arms lifted towards the sky like the mourners from ancient tragedies, reminds us of the distress death can cause. In response, a character on the right attempts to vacate the scene, knocking over flowerpots behind him. In contrast with this chaotic scene, in the center of the painting a sweeper is shown absorbed by his routine chore, appearing to reference the need for detachment when faced with the absurdity of death. Chagall created two further variants of the work. The 1911 version was more dynamic and leaning more towards cubism, and has since disappeared, while his 1923 piece is kept at Geneva’s Musée d’Art et d’Histoire. Along with The Wedding (1909) and The Birth, The Death forms part of a striking trio of paintings about the circle of life.

S.G.