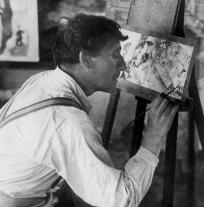

The artist’s studio is a recurring theme in art history—depicted in drawings, paintings, and photos. Looking at it through Romantic, 19th -century eyes, this fascinating place is the cradle of all artistic creation. At that time, artists were legendary, admired figures of society, and soon started setting trends1 for upper-class bourgeois and bohemians, who drew their inspiration from and fantasized about the lifestyle of the artist. Around the beginning of the 20th century, artists’ studios became an architectural model in Paris, inspiring new buildings with large glass roofs and high ceilings, bathed in light, boasting a profoundly “bohemian” interior decor—created by careful home-staging and a plethora of more of less luxurious items2. Later on, Chagall’s studio perpetuated this idea, fitting in perfectly with the collective imagination about his space. Photographs from the Marc and Ida Chagall Archive, as well as studio depictions, give us a glimpse of the atmosphere in these creative havens. Indeed, they took on many different facets depending on whether the painter was settled in Russia, France, Germany, or exiled in the United States during World War II. As it grew, Chagall’s studio morphed according to his social status and recognition as an artist—from his stay at La Ruche, a compound of studio lodgings in the Vaugirard neighborhood of Paris, from 1912 to 1914, to the construction of his villa La Colline in Saint-Paul-de-Vence where the artist settled down in 1966. These places were ideal for meeting new people and collaborating on cross-disciplinary artistic projects, transcending an extremely personal vision of the artist’s studio.

The works depicting his studio help shed light on what role and function the artist pinned on it. Chagall never painted outdoors: “I painted at my window, yet never walked down the street with my paintbox,” he asserted in Ma vie3. The artist’s studio is a pivotal place between outside and inside worlds, materialized by the window itself. In the same way as his self-portrait did, these studio representations bear witness to how Chagall considered his status as an artist—like a window into his world.

1Manuel Charpy, “Les ateliers d’artistes et leurs voisinages. Espaces et scènes urbaines des modes bourgeoises à Paris entre 1830-1914”, Histoire urbaine (“Artists’ Studios and their neighborhoods. Urban Areas and Scenes of Upper-Class Bourgeois in Paris between 1830 and 1914,” Urban History), vol. 26, no. 3, 2009, p. 43-68.

2Ibid.

3 Marc Chagall, Ma vie (My Life), Paris, republished by Stock, 1983, p. 166, in Élisabeth Pacoud-Rème, “Chagall, fenêtres sur l’œuvre” (Chagall, Window onto his Works), in Chagall, un peintre à la fenêtre (Chagall, a Painter at the Window) (Nice exhibition catalogue, Nice, Musée national Marc Chagall, June 25–October 13, 2008, Münster, Graphikmuseum Pablo Picasso Münster, November 13–March 4, 2009), Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 2008, p. 33.

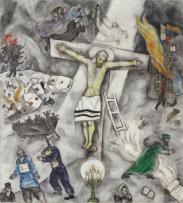

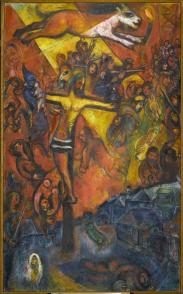

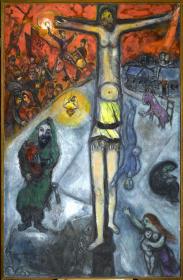

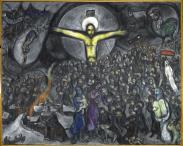

Named after the eponymous period in the Old Testament, Exodus is symbolically linked by Chagall to the destiny of the Jewish people during the war. The painting’s central figure, a yellow Christ on the cross, protects them with his arms open. On both sides of the composition, we can see scenery and iconographic elements that make up the artist’s world (Vitebsk on the bottom left; the rooster and the pendulum on the top right), chronicling the history of the Jewish people (Moses with the Tablets of the Law and the Wandering Jew, on the left and right at the bottom; the fire that symbolizes massacres, and sea travel to take refuge in Palestine, top right). This synthesis of time and place, from the microcosm to the macrocosm, is a component of Chagall’s work after the Second World War, which issued a message of universal peace. The use of black, white, and shades of gray, typical of this period and relating to the artist’s exploration of washes on paper, adds density to the composition and the play of moving masses.

A.G.