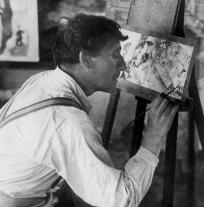

The artist’s studio is a recurring theme in art history—depicted in drawings, paintings, and photos. Looking at it through Romantic, 19th -century eyes, this fascinating place is the cradle of all artistic creation. At that time, artists were legendary, admired figures of society, and soon started setting trends1 for upper-class bourgeois and bohemians, who drew their inspiration from and fantasized about the lifestyle of the artist. Around the beginning of the 20th century, artists’ studios became an architectural model in Paris, inspiring new buildings with large glass roofs and high ceilings, bathed in light, boasting a profoundly “bohemian” interior decor—created by careful home-staging and a plethora of more of less luxurious items2. Later on, Chagall’s studio perpetuated this idea, fitting in perfectly with the collective imagination about his space. Photographs from the Marc and Ida Chagall Archive, as well as studio depictions, give us a glimpse of the atmosphere in these creative havens. Indeed, they took on many different facets depending on whether the painter was settled in Russia, France, Germany, or exiled in the United States during World War II. As it grew, Chagall’s studio morphed according to his social status and recognition as an artist—from his stay at La Ruche, a compound of studio lodgings in the Vaugirard neighborhood of Paris, from 1912 to 1914, to the construction of his villa La Colline in Saint-Paul-de-Vence where the artist settled down in 1966. These places were ideal for meeting new people and collaborating on cross-disciplinary artistic projects, transcending an extremely personal vision of the artist’s studio.

The works depicting his studio help shed light on what role and function the artist pinned on it. Chagall never painted outdoors: “I painted at my window, yet never walked down the street with my paintbox,” he asserted in Ma vie3. The artist’s studio is a pivotal place between outside and inside worlds, materialized by the window itself. In the same way as his self-portrait did, these studio representations bear witness to how Chagall considered his status as an artist—like a window into his world.

1Manuel Charpy, “Les ateliers d’artistes et leurs voisinages. Espaces et scènes urbaines des modes bourgeoises à Paris entre 1830-1914”, Histoire urbaine (“Artists’ Studios and their neighborhoods. Urban Areas and Scenes of Upper-Class Bourgeois in Paris between 1830 and 1914,” Urban History), vol. 26, no. 3, 2009, p. 43-68.

2Ibid.

3 Marc Chagall, Ma vie (My Life), Paris, republished by Stock, 1983, p. 166, in Élisabeth Pacoud-Rème, “Chagall, fenêtres sur l’œuvre” (Chagall, Window onto his Works), in Chagall, un peintre à la fenêtre (Chagall, a Painter at the Window) (Nice exhibition catalogue, Nice, Musée national Marc Chagall, June 25–October 13, 2008, Münster, Graphikmuseum Pablo Picasso Münster, November 13–March 4, 2009), Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 2008, p. 33.

Marc Chagall’s life was marked by a revolution, two wars and time in exile. His work is thus an expression of his multi-faceted political engagement and awareness, which goes against the candid image sometimes associated with his creations. Having lived in France for three years, the start of World War I came as a surprise to the artist, who was travelling to Russia at the time and was therefore forced to remain there for some time. As a sensitive witness to gruesome events, he tried to come to terms with reality—using just enough perspective and detail—through a series of monochromatic calligraphy-like drawings made with Indian ink and pencils. Wounded soldiers, nurses, abandoned elderly people, and mourning families were central to many of his works between 1914 and 1916 (The Wounded Soldier, 1914, Peasant Couple or Leaving for War, 1914).

The young Chagall was taken over by a revolutionary ardor after having been appointed fine arts commissioner for the city of Vitebsk and its region by the renowned head of the Narkompros (People’s Commissariat for Enlightenment), Anatoli Lounatcharski, whom he met in La Ruche. By reclaiming the rhetoric of the time, Chagall took it upon himself to think about art in a revolutionary manner, and put this into practice: “And if it is true that only now [when humanity has taken the road of the ultimate Revolution] can we speak of Humanity with a capital H, even more so, can Art be written with a capital A only if it is revolutionary in its essence” (Marc Chagall, 1918). During this period, he produced ethereal pieces that sounded the revolution loud and strong (Peace to the Cottages, War on the Palaces, 1918, Marching Forward, 1918).

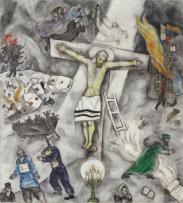

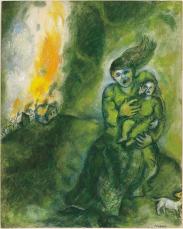

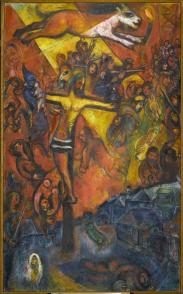

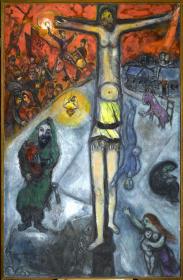

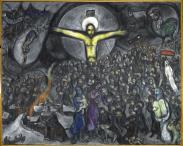

Flitting from enthusiasm to disappointment following the changes in the Soviet regime, the painter left Russia for Berlin in 1922 and settled down in France beginning in September 1923. With the Nazis having invaded France, Chagall was forced to withdraw to the region south of the Loire river. He bought an old Catholic girls’ school in Gordes in May 1940. Originally Jewish, and listed by the Nazis as a “degenerate” artist, the stigmatized painter went into exile in the United States until 1948. Depictions of the crucifixion of Jesus appeared in his works as early as 1908. The subject symbolized, amongst other things, the age-old persecutions suffered by the Jewish population and resurfaced in the painter’s work just before World War II. Christ, as a Jewish prophet, is portrayed in complex artistic compositions, including scenes of pogrom, combat, and exodus (White Crucifixion, 1938, Resistance, 1937-48, Obsession, 1943, Exodus, 1952-66) - no doubt with the desire to depict a series of human tragedies destined to carry on forever.

[1] Marc Chagall, “Iskousstvo v dni Oktiabr’skoï godovchtchiny” [Art at the time of the October birthday], in Vitebskii Listok [Vitebsk leaflets], November 7th, 1918.