The critical reception of Marc Chagall's ceramics in the 1950s

Sofiya Glukhova

From the outset, Chagall's ceramics gained recognition and met with critical acclaim, thanks notably to his group and solo shows. Two main waves of critical interest can be observed, often emerging at the same time as the exhibitions. The first was between 1950 and 1970, with three exhibitions taking place in 1952.1 The second began with a 1995 group show of artist’s ceramics at the Musée de Céramique in Vallauris and continues to the present day.2 For 25 years, from 1970 to 1995, Chagall's fragile pieces never moved. The few pieces damaged in transit probably convinced him and his wife Valentina Brodsky to stop lending them out.3 This article will focus on some of the main points of critical discourse in the 1950s that accompanied the emergence and evolution of Chagall's ceramic work, notably in articles, specialized magazines, exhibition catalogues and radio interviews.

In March-April 1950, the first public showing of Chagall's newly created ceramics was also his first exhibition at the Maeght gallery,4 the prelude to several years of collaboration. Thirteen ceramics5 were exhibited alongside 37 paintings, highlighted washes, three gouaches for The Thousand and One Nights, and original etchings for Gogol's Dead Souls. Lyrical articles published opposite poems dedicated to Chagall by Guillaume Apollinaire and Blaise Cendrars in issue 27-28 of Derrière le miroir in the 1910s6 do not mention the ceramics. However, a few weeks after the exhibition, on July 25, 1950, a French radio show7 about the artist’s ceramics aired an interview. During the show, Chagall was with renowned ceramists Émile Decœur and Josep Llorens i Artigas, both of whom had seen his early ceramics at the Maeght Gallery. The master ceramists welcomed painters to their field and highlighted the mutual enrichment resulting from their close collaboration. They encouraged artists not to limit themselves to superficial decorations or to confine themselves to merely “painting on ceramics”, and to deepen their own visual experiments by improving their technical command of the medium. The painters, for their part, breathed new life into ceramics, whose forms and decorations were tending to become repetitive, old-fashioned and, Artigas said, even obsolete. Decœur saw Chagall as one of the artists devoted to ceramics who strove to better “understand the material”, and highlighted his sensitivity.

A December 1951 article in France Illustration entitled “Des fastes byzantins de Ravenne aux mosaïques d'Audincourt” (“From the Byzantine splendors of Ravenna to the mosaics of Audincourt”) featured a photo essay on Chagall's ceramic work.8 The mosaics of Ravenna dialogued with Jean Bazaine’s for the Sacré-Coeur church in Audincourt. In addition, several pages with color illustrations of four ceramics by Chagall9 were accompanied by five photographs showing the artist at work on his pieces or going about his everyday business in Vence. Indeed, the article's author, Bernard Champigneulle ingenuously put Chagall's ceramics within broader thoughts on the revival of monumental art in the mid-20th century and the relationship between craftsmanship and the accelerated industrialization of the post-war period:

Ceramics was the first of these old craft disciplines to regain its former integrity. Artists like Lenoble and Decœur practiced ceramics with a mastery that brings their work close to the finest examples of ancient China ... We have also seen inspired artists such as Chagall and Picasso, with their curiosity for renewal, apply themselves to creating forms and decorations where their personality is expressed with no less interest than in their paintings.10.

Ceramics was linked to wall art not only from a technical point of view, when it came to faience tesserae for example, but also as the “first craft” that, in a way, paved the way for monumental creations. The revival of ceramics and contemporary wall art was part of a two-pronged movement calling easel painting into question11 and critiquing industrialization.

In a letter dated February 21, 1952, art critic Waldemar-George sent Chagall the latest issue of Art et Industrie magazine with his one-page article on the painter's ceramics entitled Chagall et la terre retrouvée12 accompanied by some illustrations.13 After tracing Chagall's movements throughout his life, Waldemar-George spoke about the artist’s move to Vence in the South of France, where his ceramics were born:

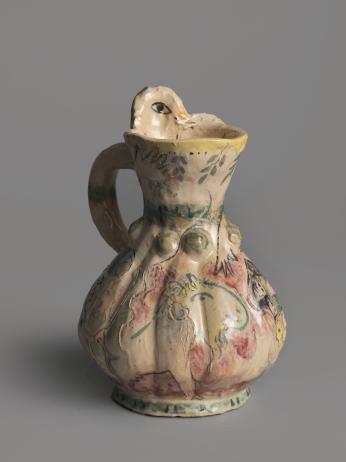

These ceramics are neither recreation nor entertainment. Chagall sees them as a way of communing with French soil, kneading it with his hands. The mark of his genius as a poet-craftsman is found here, with his winged characters, lovers embracing on a layer of clouds, animated flowers and the Orient of a thousand and one nights. Verlaine twisted the neck of eloquence. Chagall trampled prose. The handles of his vases form the arms of his astral fiancés (sic). With their shimmering colors linked to the material, his bowls and dishes are as lustrous and iridescent as Mozarabic pottery.14

Waldemar-George listed the recurring themes in Chagall's ceramics to stress their poetic side. According to the critic, his work is marked by a kind of break that prompted him to compare Chagall with Verlaine ("Verlaine twisted the neck of eloquence. Chagall trampled prose.”). But Waldemar-George's article revolves mainly around the motif of earth in the broadest sense, with the idea of uprooting oneself and putting down new roots in the South of France (“the French soil he kneads with his hands”). The theme of uprooting, suggested by the artist himself,15 structured his artistic journey and the reading of his work. He is portrayed as an artist who came from “elsewhere”16 but who defines the “universal spirit”. The double “break”, geographical and poetic, seems to contribute to a narrative more in keeping with the image of a Romantic artist, even if the work on materials is emphasized.

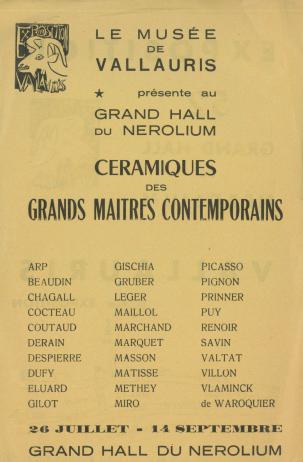

In 1952, Chagall's work was included in the fifth “Great Contemporary Masters’ Ceramics”, annual Vallauris17 potters’ exhibition at the Nérolium in Vallauris, show focusing on local production. The press was abuzz about the renewal of ceramics and the Vallauris “phenomenon”. Chagall's name often appeared alongside that of Picasso and other leading artists, as in this article in Lettres françaises, a magazine edited by Jean Paulhan and Louis Aragon: “In addition to 53 local potters, painters and poets will be showing some of their work. They are: Arp, Chagall, Cocteau, Dufy, Françoise Gilot, Masson, Pignon, Marquet, Renoir, Éluard, Matisse, Léger, Miro, Prinner.”18 The author stressed the collaboration and cross-fertilization between artists and ceramists: “The encounter between masters and local potters is rich in the sense that it frees the craftsmen from certain constraints, widening their perspectives.”19 The article also emphasized Picasso's drawing of the Golden Goat on the exhibition poster in reference to the Provencal legend of the Cabro d'Or, guardian of treasures. Echoing that tale from the High Middle Ages, the author advocated dialogue with the arts of earlier eras: Potters seem increasingly aware of the need to strip off the glitz and even return to the search of the medieval potters who knew how to translate ‘the spirit of fables’ into clay.”20

The same year, writer and art critic André Warnod, who had coined the term “École de Paris”, wrote an article about “Vallauris pottery”21 in the Arts section of Le Figaro. Warnod mentioned Chagall alongside Matisse and Picasso as practicing in Vence and wrote about his movements between different ceramic studios.

Here is a fine example of the impact artists can have on a local industry or craft. Vallauris has always been a potters' paradise because the soil is particularly well-suited to this industry, but production was slow and uncertain. Major artists have been tempted by ceramics: Matisse and Chagall in Vence, Picasso in Vallauris. That is all it took to make pottery fashionable.22

Warnod underscored the artists’ beneficial effects on pottery and, consequently, on the local economy, spurred by the growth of postwar tourism. He noted the renewal of forms and approaches, calling it “a renaissance we are witnessing in Vallauris”.

Earlier in 1952, Chagall's ceramics were featured in two monographic shows, first at the Maeght Gallery in Paris,23 then the Curt Valentin Gallery in New York.24 The painter then unveiled the lesser-known side of his recent work, the etchings for La Fontaine’s Fables published by Tériade, as well as his early sculptures and ceramics. Once again, critics were fascinated by the subtlety of the work on the material. Here is an excerpt from an article in L’Intransigeant: “Chagall the ceramist is also here. Using the happy surprises of fire, the artist has achieved often-lavish material effects. His experiments are totally different from those of another painter who recently became a ceramist: Picasso.”25 But Chagall's proximity with Picasso highlighted the distance between them.

In a shifting critical landscape where ideas intersect and respond to each other, texts in the above-mentioned Derrière le miroir occupy a place apart. Designed and published by the Maeght Gallery in close connection with its programming, each issue is a catalogue of its exhibitions while at the same time a forum for “comparing the word and the visual sign”.26 The prestigious periodical asked contemporary authors and thinkers to write about the established and emerging artists supported by the gallery. Philosopher Gaston Bachelard and author Charles Estienne wrote about Chagall for his monographic exhibition at the Maeght Gallery entitled “Marc Chagall, Céramiques, sculptures et Les Fables de La Fontaine” (“Marc Chagall, Ceramics, Sculptures and La Fontaine’s Fables)”.27

In his first article on Chagall, “La lumière des origines” (“The Light of Origins”), Bachelard analyzed the artist's work through the lens of his philosophical approach to the imagination as applied to literary and visual creation. His lines on his amazement at the ceramics of modern painters have become famous:

What a wonderful time we live in, when the greatest painters like to become ceramists and potters. So here they are, baking colors. With fire they make light. They learn chemistry with their eyes. They want the raw material to react for the pleasure of seeing it. They guess what the enamel will look like when the material is still soft, when it still looks a bit dull and barely shiny.28

Taking a sensitive, even sensual approach, Bachelard closely examined the receptiveness of the “science” of the art of ceramics to a new world offered by the visionary gaze of artists. The philosopher immediately identified Chagall, who had only been making ceramics for two years, as a master of the medium: “Marc Chagall is suddenly a master of this satanic painting, which goes beyond the surface and is part of a chemistry of depth. And in stone, in soil, in clay, he knows how to keep his vigorous animalism alive.”29 Bachelard evoked the various themes of Chagall’s iconography, his bestiary, fables, hybrid beings and biblical characters, to reveal a common essence, a “philosophy” running through all his work, whatever the medium, which is “the community of the living, the eternity of life”. He underscored the artist's mental vision and ability to bring inert matter to life: “There are so many images in Marc Chagall’s eye that for him, the past retains its full colors and the light of its origins. Once again, everything he reads, he sees. Whatever he ponders, he draws, engraves, inscribes in matter, making it burst with color and truth.”30 In Bachelard’s view, the idea of the incarnation and animation of “inert matter” characterizes his ceramic creations, marked by a form of timelessness.

Echoing the idea of a work “out of time”, in the same issue of Derrière le miroir, Charles Estienne drew a comparison between ceramics and painting, focusing in particular on Chagall's wall ceramics, which for him bring prehistoric caves to mind:

Just as at Lascaux the visual reality of a fabulous bestiary has retained its freshness and presence intact under the natural miracle of a crystallization that has acted as the best and most transparent of varnishes, so here Chagall's great ceramics, paradoxical but authentic paintings, except for the fact that trial by fire has given them a coat of enamel armor, give us an opportunity to see and touch a freshness that we now know has been preserved from that fragility whose permanent threat hangs over every fresco or easel painting.31

For Estienne, wall ceramics are a kind of painting “enlarged” in form and writing, whose colors are protected by a vitrified film. Like Bachelard, who evoked “the light of origins”, Estienne called Chagall's work “timeless” by comparing it to prehistoric art, which is introduced into modern art and criticism.32

A major 1953 monographic exhibition in Turin featured 28 of Chagall’s ceramic pieces.33 Two years later, in 1955, his large dish Noah’s Ark [L'Arche de Noé] (1951) was shown at the First International Ceramics Festival in Cannes.34 The International Academy of Ceramics, founded by Henry J. Reynaud in 1952, organizes this event, which brings together participants from 42 countries. The international festival, an event with strong diplomatic connotations, marked “the rebirth of the most uncertain, the most adventurous of all the arts”, ceramics.35

The critical discourse of the 1950s explored the phenomenon of postwar artist ceramics and attempted to grasp the specificity of Chagall’s production. Critics drew on existing norms and patterns to embrace new forms, laying the groundwork for decades to come. When the discourse went beyond biographical information or a mere list of the artist's iconographic motifs, several themes emerged. Critics, sometimes verging on a romantic interpretation, highlighted the poetic value of his work, to which ceramics lend a particular fleshiness and depth. The image of “poet-craftsman” also recurs. Chagall, who liked working with his hands alongside craftsmen, easily slipped into the role of apprentice to experienced technicians, whose presence he constantly sought. But Chagall's sensitivity to matter is what renowned ceramists like Decœur as well as writers and philosophers like Bachelard highlighted. In 1953, Chagall delivered a rare speech describing his relationship with ceramics:

This small number of pieces in ceramic, this small sample, is like a foretaste ... in a way, the result of my life in the South of France, where the meaning of this ancient craft can be felt so strongly. The very soil on which I tread is so luminous ... In these dark times of bombs and the threat of nuclear annihilation, it is particularly tempting to become attached to and merge with the soil. The roots of my homeland stretch out and mingle with the roots of my adopted country, which helps me breathe with a smile. Isn’t art like the face of my four-year-old son who expects a smile from me? When I speak of ceramics, prints or painting, all my words revolve around the material, which is abstraction itself, as long as it remains at a certain height. Even if this material is soaked in excessive sensitivity, isn’t it better to linger rather than to lose yourself in a world run by mindless habits or a prideful lack of sensitivity?36

Much more than a decorative craft practice, ceramics seems to take on the role of a receptacle for the artist's “excessive sensitivity”, capable of repairing something, and offering new dimensions and sparkles to his inner vision.

Access the search for ceramics in the online catalogue raisonné of Marc Chagall