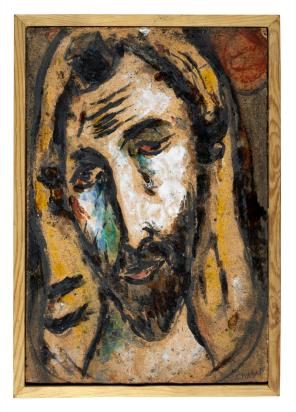

After the Second World War, Chagall, back from exile in the United States, lived first in Orgeval, then in the South of France, which came to symbolize artistic renewal for him. Like Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró and Henri Matisse, he successfully tried his hand at ceramics. Tériade and Chagall resumed Ambroise Vollard's plan to publish a Bible illustrated with etchings. Using a medium that was new for him, the artist once again turned to biblical subjects, creating a series in the early 1950s of dishes and plaques such as this Head of Christ (1951) made in Vence.

In the figure of Jesus–often depicted in his work, for example in White Crucifixion [Crucifixion blanche] (1938) –Chagall saw “an expression of the human, of Jewish sadness and pain”, adding, “Perhaps I could have painted another prophet, but after two thousand years, humanity has become attached to the figure of Jesus. For me, as a Jew, it is easier... to express the artistic truth of our suffering and state of mind to the world in this way.”1 It is therefore a humanist view that this work offers us. Christ, shown wearing a tefillin and a tallit, symbolizes the Jewish martyr, pogroms and the Holocaust, here in a postwar context. Chagall wrote, “For me, Christ has always been the archetype of the Jewish martyr.”2

The roughness of the chamotte clay contrasts with the velvety sheen of the brush-applied glaze, giving the piece sculptural relief. The tight framing of the work, conceived as a portrait, focuses attention on Christ’s intentionally wrinkled, elongated, white-highlighted face and his expression of pain and suffering, recalling the medieval ecce homo and the imago pietatis or “man of sorrows” image that was first depicted in a Byzantine icon. The connections between some of Chagall's works and the art of the icon are undeniable.3 Here, the format of the ceramic, the color yellow, the expressiveness of the eyes and the slightly tilted head recall the Angel with Golden Hair icon attributed to the Novgorod school.

Chagall was part of a revival of sacred art in France initiated by Canon Jean Devémy, who asked him and several other artists, including Germaine Richier and Georges Rouault, to decorate the Plateau d'Assy church. Devémy had already mentioned him in 1948.4 The rich material and intense black outlines recall paintings by Rouault, such as Christ (1937) at the Cleveland Museum of Art.5