Merging with the soil:

Marc Chagall and ceramics

Ambre Gauthier

“In these dark times of bombs and the threat of nuclear annihilation, it is particularly tempting to become attached to and merge with the soil.”1

Encounter with ceramics

Back in France after a seven-year exile in the United States, Chagall lived in Orgeval before moving to Provence. A four-month stay in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat with the publisher Tériade reconnected him with the Mediterranean images and sensations he had discovered on his trips to Mourillon, Toulon and Nice in 1926. He marveled at the beauty of nature, “the kingdom of flowers”,2 “the floral pigments”3 that flood the eye with bursts of color and the gentle landscapes whose shadows give birth to imaginary beings at dusk. His path took him first to Vence, where he bought the villa Les Collines in 1950, then to Saint-Paul-de-Vence, where he had his villa-studio, La Colline, built in 1966. Like many painters looking for a fresh start, Chagall moved to the South of France after the Second World War.4 This period saw the development of a rich, multidisciplinary creative process beginning with the production of ceramics and sculptures.5

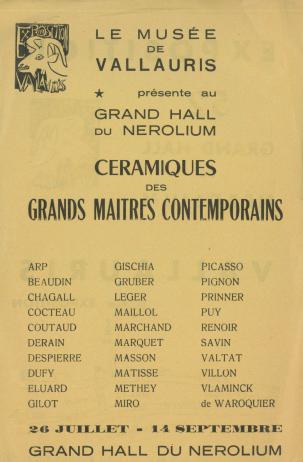

About this period of artistic ferment, Gaston Bachelard wrote: “What a wonderful time we live in, when the greatest painters like to become ceramists and potters. So here they are, baking colors. With fire they make light. They learn chemistry with their eyes. They want the raw material to react for the pleasure of seeing it.”6 In the spring of 1948, Chagall showed an interest in ceramics, especially those made by Picasso, who had moved to Vallauris in 1947 and worked at the Madoura studio.7 He asked his daughter, Ida, to pick up an issue of Cahiers d’art featuring a plate Picasso made at the Madoura workshop in Vallauris.8 While knowledge of Picasso's creations may have been crucial in sparking Chagall's interest in ceramics and Vallauris, it alone cannot explain their importance and vitality in his work for over two decades. The artist’s desire to explore the medium was probably rooted in Russian folk art, including the zoomorphic and anthropomorphic clay whistles9 he collected. It was also spurred by a 1952 trip to Greece, where he admired ancient vases with black and red figures: “I went to Delphi, the islands, Poros. I visited all the museums. In Athens they are magnificent. I contemplated the ancient paintings, the beautiful vases decorated with wild bulls on black and ochre backgrounds. What a delight they are to behold!”10 The collective enthusiasm for this technique on the part of many artists living in the South of France11 fueled creative competition and a first-rate cultural phenomenon that sparked a decorative arts revival and a reassessment of artisanal practices. Chagall took part in this movement with gusto while keeping his distance from groups and decorative trends to blaze his own trail and follow his own inspirations, emphasizing “chemistry”12 and dialogue with the material’s energy, which takes from as much as it gives to the artist, forging continuous links between past and present. His footsteps set him on “a path from a place no one comes from to a place where no one goes”13, which in late 1949 led him to what Virginia Haggard called “dirty work”14, ceramics and sculpture. This marked the start of a long period of ceramic creation punctuated by cycles of intense work and breaks15 that lasted until 1972, resulting in 350 one-off pieces16 of unmatched formal inventiveness.

Trial by fire

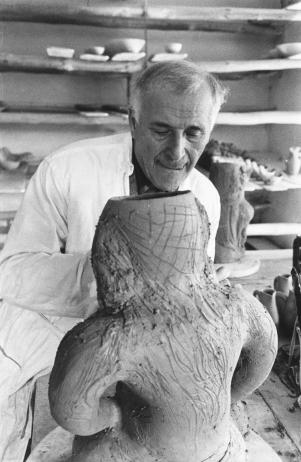

By exploring the technique of ceramics, Chagall embraced a new medium that took him down unmapped paths, leading to both physical and symbolic creation. With his hands plunged into the soil and his eyes caressing the sensitive, vibrant material free of human intervention, he sought to “give shape to the marvelous”17, to explore all the cavities and furrows on the surface of the wet clay and to follow in the footsteps of the craftsmen who had gone before him for thousands of years. While experimentation with the most daring shapes and firings was at the heart of his practice, he never forgot painting. It remained his only goal, nurtured by constantly moving back and forth between techniques,18 which contributed to the diversification and renewal of his pictorial approach on a daily basis. Ceramics was a means to renew the dialogue with nature in the simplicity of its origins and the beauty of its flaws, tending towards a form of artisanal authenticity without convention, decorative effects or the easy way out: “My work with ceramics here in the South of France is a different experience, a kind of approach to nature that avoids, if possible, superfluous decoration which, it seems to me, is worthy neither of the clay nor of the fire through which it passes.”19 He continued: “Working with clay, facing the intrinsic difficulties of the material and techniques, also means putting one's art at the service of an ancestral physical and symbolic anchorage and beginning to speak ‘the language of hidden things’.”20 The mastery of fire necessary for creating ceramics is at the origin of a creative and mystical power that, since the dawn of time, has put those who control the flames above their peers: “Some in the midst of this blind, staggering crowd understand the hidden things. They mutely sense the great tremors of the body, the sudden decrease of blood; they possess the gift, the strength ... they carry decades of pain and joy inside them. They know fire, they have it within them, they master the flames.”21 Fire symbolically illuminates possible paths, shining light into the shadows of consciousness. It has both the spark of life and the power to destroy.22 Chagall had a deep respect for fire. An eternal apprentice, he felt humbled in its presence and before the moving, shifting clay that could not be easily tamed: “In ceramics and sculpture, what do I bring to matter, to God's soil, to God's fire, to leaves, to bark, to light? Perhaps it is the memory of my father, my mother, my childhood and my family for a thousand years... perhaps it is also my heart. One must be humble and submissive before the material!”23

“Defector from the homeland”

After a seven-year exile in the United States, Chagall's return to France was accompanied by a desire to become one with the adopted homeland where he had lived and created from 1911 to 1914 and 1923 to 1941: “I came to France with earth still clinging to the roots of my shoes. It took a long time for it to dry and fall off. When that happened to me, independent of my will, I had to find another reality. I found it in the landscapes of France, the flowers of the Midi, the horizons of Peïra-Cava, the earth of Gordes and Roussillon, the deep reds of Mexico ... But this is only possible for those who have kept their roots. Keeping the earth on your roots or to find new ones is a real miracle.”24 Chagall did not forget his disillusionment with France during the war years,25 but making ceramics renewed his desire to integrate into French culture, both artistic and artisanal. At the same time, working with clay provided him with a symbolic connection to the soil of his birthplace, Vitebsk: "It suddenly seems to me that this light-colored earth calls out from afar to the dark earth of my native Vitebsk," 26.” The vase The House [La Maison] (1952)27 is a tangible embodiment of the connection Chagall made between the soil of the Mediterranean and that of his native land. Through ceramics, the soils of past and present leap across geographical boundaries, dialoguing with each other and merging in the development of a groundbreaking visual language: “My only country/Is the one inside my soul/I enter it without a passport.”28 Sinking his hands into clay and feeling its vibrations, hearing the age-old song of all the migrations and exiles it remembers and bears witness to through its material presence, shaping and transforming the material to follow the contours of a vivid imagination deeply marked by the upheavals of recent times, are all sensory and artistic experiences that connected Chagall to this “material steeped in excessive sensitivity”.29 Both the material and the artist share this sensitivity, which spreads and lives on in all the “exiles from the soil”,30 men and women who have been uprooted from their homes, continually floating in the air and between times, poised to flee again, like the wandering Jews and the Luftmenschen so often seen in Chagall’s paintings.

In the footsteps of the Golem

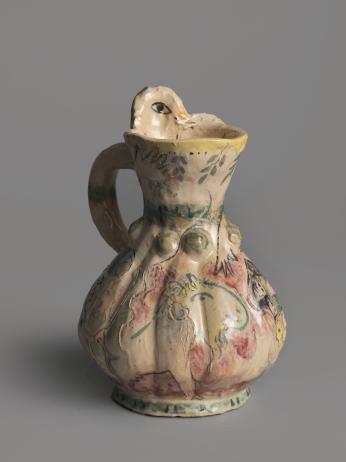

Some of the anthropomorphic and zoomorphic beings Chagall created, half-monsters, half-apotropaic figures, seem unrelated to any known form of life. These weird shapes, born of a totally unleashed imagination and the liberated instinct of the hands that shaped them, are much more than an iconographic extension of the artist’s paintings. Giving birth from clay to forms and beings from the far reaches of the mind has deep ramifications in the legend of the Golem, which can be roughly translated from Hebrew as “shapeless mass”, a mythical creature from Jewish culture and the Talmud. According to legend, a clay creature can be molded and given life by incantations, becoming a mystical double that does its creator’s bidding.31 Emerging from the Earth’s life forces, the Golem has the ability to protect or destroy, depending on its creator’s arcane secrets and intentions. In the Sefer Yetsirah (“Book of Creation”), God is described as “the great potter shaping the world”,32 further strengthening the link between divine and artistic creation. The submission of the creature/work to its creator’s relative goodwill offers a glimpse of possible conditions for emancipation and liberation. The act of creation at the heart of the legend is a powerful metaphor for artistic creation and the artist’s inner struggle to give birth to inanimate forms and materials that may prove untamable and resistant to every manner of domination. The image of the artist breathing life into his or her paintings or ceramics, giving “shape to the marvelous”,33 powerfully echoes the legendary force that animates figures in clay or loam.34 While “all artists are makers of Golems”,35 Chagall, unlike other painters,36 never explicitly depicted the creature.37 However, some of his clay beings (The Chimera [La Chimère] (1954)

From one studio to another

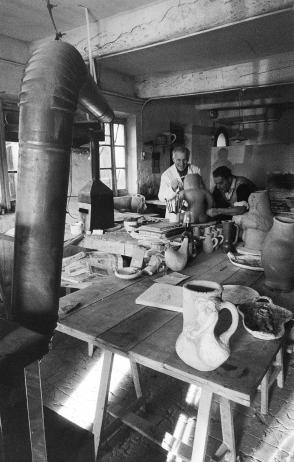

Between 1949 and 1972, Chagall made 350 ceramics38 in several studios39 in the South of France. The complexity of the time he spent in these workshops lies in the fact that it was neither linear nor continuous. Chagall worked in cycles with several craftsmen simultaneously40 to carry out a variety of technical experiments suiting the specific features and styles of each piece. Given the current research, a plate called Evening [Le Soir] (1949) is the first piece he made. Lacking a potter's mark, its exact attribution to a studio remains a matter of guesswork, although stylistically it bears a resemblance to the pieces made at Poterie des Remparts in Antibes,41 which seems to be the first place Chagall worked in 1949. Assisted by several employees, including painter and ceramist Serge Ramel42 and Suzanne Ribemont,43 Mme. Bonneau44 probably ran the studio, where the artist made his first ceramics, training his eye and hand. While it is difficult to give a precise account of this collaboration,45 13 pieces are stamped “Poterie des Remparts”. A look at this sample of Chagall's work in Antibes reveals the shapes and the decorations’ rudimentary simplicity. They are more akin to a painterly approach than to a genuine ceramic practice, a classic example of painting on ceramics practiced in the early 1950s by many artists trying their hand at the technique.46 There are no bold shapes or any real work on the material. An evenly applied enamel glaze unifies the decoration and its support without taking advantage of the clay’s grain or velvetiness, putting it and the subject on the same level (Judith and Holofernes [Judith et Holopherne] (1950)). These early, modest, subdued works were directly influenced by the book projects Chagall had been working on since 1950, La Fontaine's Fables and the Bible,47 which gives them an illustrative dimension. In 1952, Chagall worked with Serge Ramel at Poterie des Remparts before switching to Poterie du Peyra in Vence48 while conducting firing trials at the Lebasque studio in Clausonnes.49 In 1954, he frequented the Art feu céramiques et faïences d'art A. & R. Roux studio in Juan-les-Pins.50 The artist occasionally called on ceramists Marius Giuge51 (The Conversation [La Conversation] (1958)) and Michel Muraour52 (Man and Bird [Homme et oiseau] (1972) and Self-portrait [Autoportrait] (1972)). To continue these experiments and put them into a more personal context, in 1956,53 through the intermediary Roland Brice, he requested a quote for the installation of a kiln54 in his villa, Les Collines, in Vence. It is unknown if the kiln was ever built, but the request attests to Chagall’s desire to make ceramics in his own studio and to have different media physically and simultaneously interact in the same space. This is corroborated by the fact that he painted some Madoura pieces in his home studio.55 Chagall’s longest and most productive collaboration was with Madoura in Vallauris, where he made hundreds of one-off ceramics from 1951 to 1971. The studio was a legendary place that alone embodied the spirit of Vallauris and its potters. Nevertheless, it did not seem to meet all of his requirements,56 for he kept on experimenting at other studios at the same time.

Vallauris, land of potters

In the late 1940s, Vallauris, an agricultural area marked by slopes planted with bitter orange trees whose blossoms are used to make neroli essence, was, according to artist Jean Derval, “paradise”.57 Its abundant nature, exuding citrus, zesty fragrances, borders the hills of a traditional village home to pottery studios58 abandoned by the late 1930s.59 After the war, young artists from all over France, drawn to the area and its home-grown craft traditions, moved to Vallauris, including Robert Picault, Roger Capron, Jean Derval and Jean Rivier. Seeking to revive local ceramic-making traditions by developing their own styles, they gradually became part of local life, taking over old, disused studios. A sunny, self-reliant bohemian community emerged, populated by adventurous young artists who enjoyed the simplicity and ruggedness of local life, far from the hustle and bustle of cities: “Vallauris

Chagall at Madoura

Chagall made most of his ceramics at the Madoura studio in Vallauris,69 including the wedding service (1952)70 and “sculpture-vases” in collaboration with Suzanne Ramié71 from 1951 to 1972. Founded in 193872 and run by Suzanne and Georges Ramié, Madoura was the epicenter of ceramics creation in Vallauris. The studio grew famous and successful due to artists' ceramics, especially those of Picasso, who arrived in 1947. Like many other artists, including Matisse and Victor Brauner, Chagall arrived in Madoura with the aim of blazing his own trail but quickly realized that Picasso’s presence would influence his experiments. While the two artists met each other at Madoura, they did not become friends. Rivalry and misunderstandings seemed to overshadow their mutual admiration. Later, Chagall wrote: “We often ran into each other in Ramié's Vallauris studio, where both of us worked on ceramics. Potters created dozens of birds and other subjects for him. He would touch up the neck or the foot with his finger on the spot before instantly moving on to the next series, probably always caught up in the feverish desire to produce as much as possible. His skill was astonishing, but so was the decorative power of his lines and spots, which were kept to a minimum so that the workers could make copies right there and then. That is how obsessed he was with quantity.”73 In contrast, Chagall focused on one-off pieces. The artist seemed unsatisfied with the simple plates and dishes he designed at Madoura in 1951 and decorated with oxides and slips (Nude with Rooster II or Woman with Rooster [Nu au coq II ou Femme au coq] (1951)), describing them as “paintings on ceramics”.74 This explains his simultaneous trials in various studios: “The Madoura ceramics are successful but they would’ve looked just as good on canvas or paper. The clay isn’t rich. It's the watercolor painting that matters, and after all, that's not what ceramics are about.”75 Picasso’s presence seemed to draw Chagall to the studio in the first place, but it gradually became overwhelming: “Papa made another half-dozen plates there but now he's disgusted again, for good I think, because Picasso’s spirit permeates everything. The workers themselves are worn out, a bit jaded and scornful, and it's really disheartening to see graveyards of Picasso imitations everywhere.”76 Not wanting to add to the “graveyards of imitations”, Chagall worked mainly with artisans Jules Agard (1905-1986) and Yvan Oreggia (1936- ) to develop a more personal style of ceramics without Picasso's vocabulary. Agard, an outstanding potter and Madoura’s technical director, contributed his expertise to the creation of complex and monumental pieces77 (The Peasant at the Well [Le Paysan au puits I] (1952); Large Figures [Grands personnages] (1962); The Crossing of the Red Sea, Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Grâce, Plateau d'Assy [La Traversée de la mer Rouge, Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Grâce, le plateau d'Assy] (1956)). Some were molded by Loris Cerulli78 (1906-1983). The decoration was made in collaboration with Yvan Oreggia, then Dominique Sassi, under the watchful eye of Suzanne Ramié. Portrayed as a “loner”79 at Madoura, with Picasso “monopolizing”80 the studio, Chagall went there mainly when the latter was away,81 working on existing forms or designing his own, modeling some of them by hand. He rejected the smoother, more regular turned forms82 that were Picasso’s trademark. Chagall created one-off pieces called “sculpture-vases”83 featuring whimsical, hybrid shapes. They move and encourage us to reconsider the established boundary between ceramics and sculpture through innovative work on volume and its presence in space. The use of enamels on both utilitarian84 and almost-sculptural pieces deepens their textures and chromatic intensity85 in line with the artist’s pictorial approach. Alternating between shimmering brilliance (Persian plate [Assiette persane] (1955)) and the naturally matte surface of clay (Elijahs Chariot [Le Char d'Élie] (1951); The Lovers and the Beast [Les Amoureux et la Bête] (1957)), Chagall did not always seem to heed the advice he received from craftsmen in the studio.86 This was undoubtedly due less to a defiant, “go-my-own-way” attitude than to a deep need to confront the clay’s fragility, recognize and transform firing accidents and be moved by the beauty of the resulting irregularities. Guided by his instinct and the power of touch, Chagall’s quest for the point of no return set him apart from the other artists at Madoura: “This soil, like the craft itself, is not easily tamed. The firing was enough to make me pull my hair out. Sometimes I was grateful for the result, sometimes it was grotesque and tragic.”87 These technical explorations, pushed ever further by the addition of hand-modeled elements glued with barbotine or by wire-cut shapes (White Vase and Hand [Variante en blanc des Amoureux en rose avec une main] (1962)), sometimes covered in pastel, chalk and tempera after firing, are specific to Madoura’s experimental spirit and Suzanne Ramié’s bold approach. Chagall’s “work in the mass”,88 removing as much as adding to the material, constantly plays with the key ideas of improvisation and irretrievable mistakes, with imperfection and humility,89 as each firing can reduce the creation to nothing. By constantly taking risks, with light on his fingertips, Chagall merged with the soil the better to face his times, as fragile and brittle as the clay he handled: “The very soil on which I tread is so luminous. It looks at me tenderly, as if it were calling me.”90

Access the search for ceramics in the online catalogue raisonné of Marc Chagall