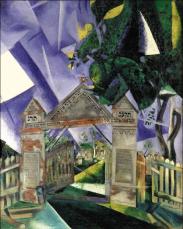

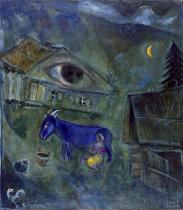

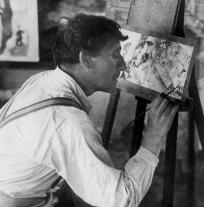

The artist’s studio is a recurring theme in art history—depicted in drawings, paintings, and photos. Looking at it through Romantic, 19th -century eyes, this fascinating place is the cradle of all artistic creation. At that time, artists were legendary, admired figures of society, and soon started setting trends1 for upper-class bourgeois and bohemians, who drew their inspiration from and fantasized about the lifestyle of the artist. Around the beginning of the 20th century, artists’ studios became an architectural model in Paris, inspiring new buildings with large glass roofs and high ceilings, bathed in light, boasting a profoundly “bohemian” interior decor—created by careful home-staging and a plethora of more of less luxurious items2. Later on, Chagall’s studio perpetuated this idea, fitting in perfectly with the collective imagination about his space. Photographs from the Marc and Ida Chagall Archive, as well as studio depictions, give us a glimpse of the atmosphere in these creative havens. Indeed, they took on many different facets depending on whether the painter was settled in Russia, France, Germany, or exiled in the United States during World War II. As it grew, Chagall’s studio morphed according to his social status and recognition as an artist—from his stay at La Ruche, a compound of studio lodgings in the Vaugirard neighborhood of Paris, from 1912 to 1914, to the construction of his villa La Colline in Saint-Paul-de-Vence where the artist settled down in 1966. These places were ideal for meeting new people and collaborating on cross-disciplinary artistic projects, transcending an extremely personal vision of the artist’s studio.

The works depicting his studio help shed light on what role and function the artist pinned on it. Chagall never painted outdoors: “I painted at my window, yet never walked down the street with my paintbox,” he asserted in Ma vie3. The artist’s studio is a pivotal place between outside and inside worlds, materialized by the window itself. In the same way as his self-portrait did, these studio representations bear witness to how Chagall considered his status as an artist—like a window into his world.

1Manuel Charpy, “Les ateliers d’artistes et leurs voisinages. Espaces et scènes urbaines des modes bourgeoises à Paris entre 1830-1914”, Histoire urbaine (“Artists’ Studios and their neighborhoods. Urban Areas and Scenes of Upper-Class Bourgeois in Paris between 1830 and 1914,” Urban History), vol. 26, no. 3, 2009, p. 43-68.

2Ibid.

3 Marc Chagall, Ma vie (My Life), Paris, republished by Stock, 1983, p. 166, in Élisabeth Pacoud-Rème, “Chagall, fenêtres sur l’œuvre” (Chagall, Window onto his Works), in Chagall, un peintre à la fenêtre (Chagall, a Painter at the Window) (Nice exhibition catalogue, Nice, Musée national Marc Chagall, June 25–October 13, 2008, Münster, Graphikmuseum Pablo Picasso Münster, November 13–March 4, 2009), Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 2008, p. 33.

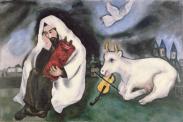

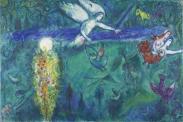

The sacred, linked to spirituality and referring to both the invisible and the intangible, is a key concept in Marc Chagall’s body of work. In a universal quest, the artist explored the boundaries between Jewish and Christian religions. Having grown up within the Hasidic Jewish community of Vitebsk, he deviated from the taboo on depiction, delving into his origins in a search for the divine and its transcendency. In line with his era, Chagall depicted the Prophets “despite the fact that the atmosphere [...] is not prophetic.” In 1931, he produced a series of works, ordered by Ambroise Vollard starting in 1925, to illustrate an edition of the Bible, an endless source of inspiration, poetry, and political discourse for the artist. Marc Chagall takes ownership of the text, interpreting it freely, and lending modernity and a new, militant strength to the tale in order to draw from it, above all, a “universal humanist message.” When the painter uses the religious theme of the Crucifixion (White Crucifixion, 1938), he reveals, like a premonition, the martyr represented by Christ, imbued with the horrors committed against the Jewish people in Europe during WWII. Chagall reinvented his approach to the sacred throughout his body of work. As soon as he returned to France, in the early 1950s, he took part in the rebirth of sacred art along with other artists, including Henri Matisse, at the behest of Father Marie-Alain Couturier. He did this by sculpting the ceramic Crossing of the Red Sea for the Chapel of Assy (1956) and creating the Biblical Message cycle (1960-1966), initially planned for the Chapelle du Calvaire in Vence. The “wonderful colorist” Marc Chagall’s deliberate turn towards monumental art led him to explore all the ranges of stained glass, whose colors and light adorned the windows of sacred and secular architecture, be it established or contemporary. He created more than seventy stained glass works, all the way to the end of his life, including those of the synagogue of the Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem, the Metz Cathedral in collaboration with Simon-Marq’s studio in the 1960s, and, in the late 1970s, the stained glass windows of the Art Institute of Chicago.