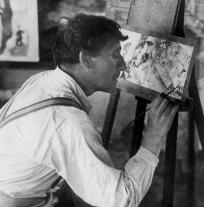

The artist’s studio is a recurring theme in art history—depicted in drawings, paintings, and photos. Looking at it through Romantic, 19th -century eyes, this fascinating place is the cradle of all artistic creation. At that time, artists were legendary, admired figures of society, and soon started setting trends1 for upper-class bourgeois and bohemians, who drew their inspiration from and fantasized about the lifestyle of the artist. Around the beginning of the 20th century, artists’ studios became an architectural model in Paris, inspiring new buildings with large glass roofs and high ceilings, bathed in light, boasting a profoundly “bohemian” interior decor—created by careful home-staging and a plethora of more of less luxurious items2. Later on, Chagall’s studio perpetuated this idea, fitting in perfectly with the collective imagination about his space. Photographs from the Marc and Ida Chagall Archive, as well as studio depictions, give us a glimpse of the atmosphere in these creative havens. Indeed, they took on many different facets depending on whether the painter was settled in Russia, France, Germany, or exiled in the United States during World War II. As it grew, Chagall’s studio morphed according to his social status and recognition as an artist—from his stay at La Ruche, a compound of studio lodgings in the Vaugirard neighborhood of Paris, from 1912 to 1914, to the construction of his villa La Colline in Saint-Paul-de-Vence where the artist settled down in 1966. These places were ideal for meeting new people and collaborating on cross-disciplinary artistic projects, transcending an extremely personal vision of the artist’s studio.

The works depicting his studio help shed light on what role and function the artist pinned on it. Chagall never painted outdoors: “I painted at my window, yet never walked down the street with my paintbox,” he asserted in Ma vie3. The artist’s studio is a pivotal place between outside and inside worlds, materialized by the window itself. In the same way as his self-portrait did, these studio representations bear witness to how Chagall considered his status as an artist—like a window into his world.

1Manuel Charpy, “Les ateliers d’artistes et leurs voisinages. Espaces et scènes urbaines des modes bourgeoises à Paris entre 1830-1914”, Histoire urbaine (“Artists’ Studios and their neighborhoods. Urban Areas and Scenes of Upper-Class Bourgeois in Paris between 1830 and 1914,” Urban History), vol. 26, no. 3, 2009, p. 43-68.

2Ibid.

3 Marc Chagall, Ma vie (My Life), Paris, republished by Stock, 1983, p. 166, in Élisabeth Pacoud-Rème, “Chagall, fenêtres sur l’œuvre” (Chagall, Window onto his Works), in Chagall, un peintre à la fenêtre (Chagall, a Painter at the Window) (Nice exhibition catalogue, Nice, Musée national Marc Chagall, June 25–October 13, 2008, Münster, Graphikmuseum Pablo Picasso Münster, November 13–March 4, 2009), Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 2008, p. 33.

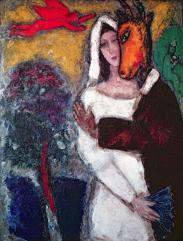

Marc Chagall’s works, populated with lovers, accord a central position to love and the union of beings. Embracing each other, flying through the air, or dancing, pairs of humans, animals, or hybrid creatures punctuate his compositions and help create a pictorial world where love reflects the aspiration of original unity. As early as 1911-1912, variations on Adam and Eve and on Homage to Apollinaire called into question love’s image in the complexity of duality and male-female complementarity, with the couple depicted as a two-headed hybrid creature with a single body. Attesting to the search for an idealized fusion of masculine and feminine, the theme finds its extension in the portraits or double profiles painted by the artist throughout his career. Tied to the story of creation, the couple isn’t just intended to portray love; paradise lost and original sin may express an imbalance or a subjacent threat. In Lovers with Pole (1951), the pair of lovers is bound to a pole, seemingly destined for an impending sacrifice. Love is put to the test of an unstable, dangerous world as represented by the upside-down village sketched in the background. The pictorial guiding theme—in search of the other, of an alter ego—also takes shape through the inspiring figures of the women who shared his life: Bella, Virginia, and Vava. In his numerous portrayals of female forms, the artist questions the complementarity of two beings coming together to form one, and the preponderant role of union and marriage, which are both subjects and elements of composition. In Midsummer Night’s Dream (1939), a bride dressed in a white gown is joined to a goat-man with alert and uniquely gentle eyes, protecting his beloved with a tight grasp. Like unexpected moments of recognition between beings, the couple draws its hybrid nature from ancient mythology and the animism of Russian popular culture, extending its exploration of the forms and metamorphoses of love. Later on, in vast, colorful canvasses, the Biblical Message cycle (1960-1966) depicted universal love through a grand biblical and humanist narration.