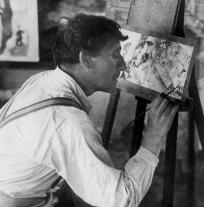

The artist’s studio is a recurring theme in art history—depicted in drawings, paintings, and photos. Looking at it through Romantic, 19th -century eyes, this fascinating place is the cradle of all artistic creation. At that time, artists were legendary, admired figures of society, and soon started setting trends1 for upper-class bourgeois and bohemians, who drew their inspiration from and fantasized about the lifestyle of the artist. Around the beginning of the 20th century, artists’ studios became an architectural model in Paris, inspiring new buildings with large glass roofs and high ceilings, bathed in light, boasting a profoundly “bohemian” interior decor—created by careful home-staging and a plethora of more of less luxurious items2. Later on, Chagall’s studio perpetuated this idea, fitting in perfectly with the collective imagination about his space. Photographs from the Marc and Ida Chagall Archive, as well as studio depictions, give us a glimpse of the atmosphere in these creative havens. Indeed, they took on many different facets depending on whether the painter was settled in Russia, France, Germany, or exiled in the United States during World War II. As it grew, Chagall’s studio morphed according to his social status and recognition as an artist—from his stay at La Ruche, a compound of studio lodgings in the Vaugirard neighborhood of Paris, from 1912 to 1914, to the construction of his villa La Colline in Saint-Paul-de-Vence where the artist settled down in 1966. These places were ideal for meeting new people and collaborating on cross-disciplinary artistic projects, transcending an extremely personal vision of the artist’s studio.

The works depicting his studio help shed light on what role and function the artist pinned on it. Chagall never painted outdoors: “I painted at my window, yet never walked down the street with my paintbox,” he asserted in Ma vie3. The artist’s studio is a pivotal place between outside and inside worlds, materialized by the window itself. In the same way as his self-portrait did, these studio representations bear witness to how Chagall considered his status as an artist—like a window into his world.

1Manuel Charpy, “Les ateliers d’artistes et leurs voisinages. Espaces et scènes urbaines des modes bourgeoises à Paris entre 1830-1914”, Histoire urbaine (“Artists’ Studios and their neighborhoods. Urban Areas and Scenes of Upper-Class Bourgeois in Paris between 1830 and 1914,” Urban History), vol. 26, no. 3, 2009, p. 43-68.

2Ibid.

3 Marc Chagall, Ma vie (My Life), Paris, republished by Stock, 1983, p. 166, in Élisabeth Pacoud-Rème, “Chagall, fenêtres sur l’œuvre” (Chagall, Window onto his Works), in Chagall, un peintre à la fenêtre (Chagall, a Painter at the Window) (Nice exhibition catalogue, Nice, Musée national Marc Chagall, June 25–October 13, 2008, Münster, Graphikmuseum Pablo Picasso Münster, November 13–March 4, 2009), Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 2008, p. 33.

In Marc Chagall’s body of work, acrobats, jugglers, musicians, trapeze artists, and trick riders perform in compositions that are happy and colorful—at first glance. But this enchanted world conceals a metaphorical and symbolic dimension of tragedy, where laughter mingles with drama. As reminiscences of the traveling circuses Chagall encountered in his youth in Russia, the theme of the circus emerged in his work as early as the 1910s. Drawings created as soon as he arrived in Paris bear witness to his visits to the Cirque Medrano. Like Pablo Picasso, Chagall associated the world of circus performers with the tragedy of existence: “The circus is the most tragic representation in my mind. Through these centuries, it is the highest-pitched cry in man’s search for amusement and joy.” Man escapes his daily life in the enchanted interlude of the circus, where the marveling of spectators is equaled only by the extent to which the stage artists are suffering. Commedia dell’arte (1959, Frankfurt Theater) turns the circus ring into a mirror of contemporary society, through which the acrobats and musicians sound a unanimous signal of European reconstruction. Sacred and secular dimensions cohabitate within the canvasses, where the acrobats take on biblical proportions: “I’ve always considered clowns, acrobats, and actors to be tragically human. To me, they resemble the characters of some religious paintings. Even today, when I paint a crucifix or another religious scene, I experience the same feelings as when I painted circus performers.”