Marc Chagall and the ceramic studios in the South of France

Quitterie du Vigier

“These few pieces, these few samples of ceramics are a sort of foretaste: the result of my life in the South of France, where one feels so strongly the significance of this craft. The very earth on which I walk is so luminous. It looks at me tenderly, as if it were calling me

In 1949, Chagall moved to the South of France, where he discovered the light that became a source of inspiration. He tried his hand at ceramics in studios that were part of an ancestral southern pottery tradition historically enriched by trade and the arrival of Italian craftsmen. Between the 16th and 19th century, southern domestic pottery circulated and was traded. Particular skills were developed in Provence. In Biot, immigrants from the Genoese Riviera brought their own techniques and the town became known for its jars.2 When Italian families massively arrived in Vallauris in the 16th century, local potteries increased their output3 and the town gradually became a major production site thanks to the quality of its refractory (heat-resistant) earth4 until the 19th century, when most manufacturing was industrialized. In the late 1930s, after potteries had declined due to competition from aluminum5, a new generation of artisans, including Suzanne Ramié at the Madoura studio, reversed the town’s fortunes.

With Picasso setting an example at the Madoura studio in Vallauris in 1947, Chagall, like other artists such as Henri Matisse and Victor Brauner, was keen to try his hand at ceramics. Their ceramics broke down the boundaries between art and craft. Chagall's are extremely rich, amounting to over 300 pieces.6

A study of the pieces and the Marc and Ida Chagall Archives reveals that Chagall frequented several local potters' workshops in addition to Madoura. The latest research on these ceramic studios has documented Chagall's activity across various production sites in the South of France, including Antibes, Vence and Vallauris.

Marc Chagall and potters in the South of France

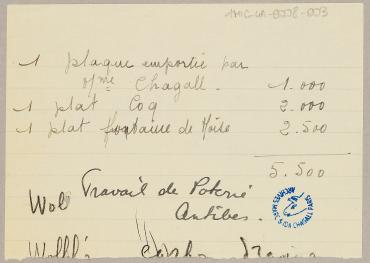

It is highly likely that Chagall began making ceramics in 1949 with Jeanne Bonneau7 at the Poterie des Remparts in Antibes,8 where painter and ceramist Serge Ramel worked in 1948.9 He made at least 13 pieces there bearing the mark “Poterie des Remparts”, including two dishes in a series of 12 featuring La Fontaine’s fables:10 Le Coq et la Perle 1317]] and La Fontaine’s Fables: The Fox and the Stork [Fables de La Fontaine : Le Renard et la Cigogne] (1950). An invoice11 also mentions three vases, a plate and two dishes (“Rooster” and “Moses’s Fountain”, probably Moses at the Spring [Moïse à la source] (1950), fig.1 and 2). The Poterie des Remparts pieces are quite simple. The artist worked with the material, “drawing” figures and motifs with slips and oxides and playing with the enamel’s gloss, as in Judith and Holofernes [Judith et Holopherne] (1950), which resembles a “ceramic painting”,12 to use Charles Estienne’s expression.

Chagall worked with Serge Ramel, who later moved to the Poterie du Peyra in Vence13 and probably used the kiln at the Lebasque studio in Clausonnes. His production there was destroyed in a fire.14 Then, Chagall frequented the Art feu céramiques et faïences d'art A. & R. Roux studio in Juan-les-Pins, as attested by a letter of payment from 195415 and an invoice for a plaque and five dishes.16

A study of Chagall's ceramics also reveals his collaboration with the ceramist Marius Giuge, probably for the use of forms, on at least four white clay pieces decorated with oxides on enamel, such as The Conversation [La Conversation] (1958). The last two ceramics, Man and Bird [Homme et oiseau] (1972) and Self-portrait [Autoportrait] (1972), were made in 1972 in collaboration with ceramist Michel Muraour.17

The diversity of studios, encounters and collaborations reveal Chagall’s desire to broaden his artistic practice and try his hand at this new technique.

Chagall at the Madoura studio in Vallauris

Chagall worked at the Madoura studio run by Suzanne and Georges Ramié and took part in the revival of ceramics in Vallauris. Suzanne reinvented culinary pottery with help from the studio's first employee, potter Jules Agard.18 In 1947,19 Picasso began working at Madoura, helping to make it famous. That is surely what led Chagall to the studio. He probably began working there in 1951.20 While it is currently impossible to put an exact number on the pieces produced at Madoura,21 many photographs document this fruitful collaboration (fig. 3).

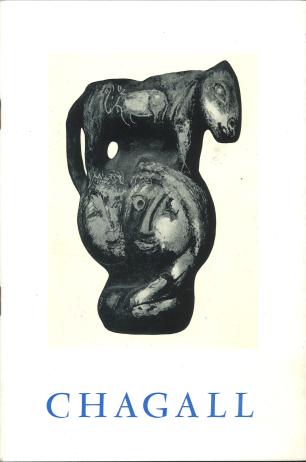

Chagall made drawings and studies before producing ceramics at Madoura (the studio’s gallery exhibited a selection of preparatory works in 1962, fig. 4). The artist decorated utilitarian ceramics (plates, dishes, vases and jugs) but also made plaques, wall tiles and shaped pieces. The vases and shaped pieces, like Lovers and the Beast [Les Amoureux et la Bête] (1957), lean towards sculpture. In fact, the works Chagall called “vase-sculptures”22 showcase all of the virtuosity and expertise available at Madoura.

To create his pieces, the artist bought clay from L’Union and paints and enamels from the Hospied factory23 run by M. Cox.24 Loris Cerulli designed the molds.25 Yvan Oreggia assisted Chagall with the colors, slips and enamels.26 His sources of inspiration ranged from Russian art to pre-Hispanic ceramics.27

In 1951, Chagall collaborated with the Madoura studio on the table service he designed for his daughter Ida’s wedding. It included 77 white enameled pieces28 featuring motifs painted in cobalt blue and iron oxides.29 In 1956, he created the ceramic mural The Crossing of the Red Sea, Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Grâce, Plateau d'Assy [La Traversée de la mer Rouge, Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Grâce, le plateau d'Assy] (1956) (fig. 5), a monumental work for the baptistery of Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Grâce church in Plateau d'Assy designed by Maurice Novarina and built between 1937 and 1946. Abbot Jean Devémy and Father Marie-Alain Couturier, who initiated the construction of the church and aimed to renew sacred art in France, asked artists Pierre Bonnard, Henri Matisse, Germaine Richier and Chagall30 to decorate the building. Chagall collaborated with Raymond Legrand31 on the mural, which consists of 90 terracotta tiles.

Chagall frequented several ceramists' workshops, sometimes simultaneously, including the historic Madoura studio, and relied on the skills of local craftsmen. For Chagall, who travelled, witnessed the tragedies of the 20th century and lived in exile in the United States during the Second World War, working with earth meant being anchored “in a practice that goes back millennia, to immerse oneself in the history of a country, to become one with it and to unite with the soil in order to make a fresh start.”32 He wrote: "When I came to France, soil was still clinging to the roots of my shoes. It took a long time for it to dry and fall off.”33 The artist began working in ceramics slightly before, at the same time as sculpting, revealing a command of the third dimension.

Access the search for ceramics in the online catalogue raisonné of Marc Chagall