The Story of Three Paintings. From a Monumental Work to a "Triptych" Between France and the United States (1937-1952)

Eva Belgherbi

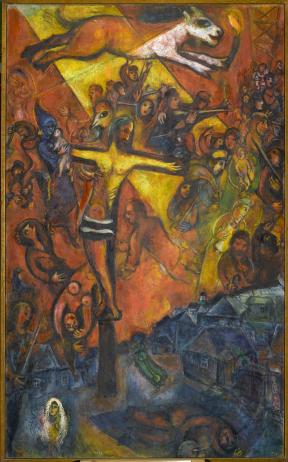

This article delves into the story of three paintings, "Resistance" (1937-1948), "Resurrection" (1937-1948) and "Liberation" (1937-1952), held at the Marc Chagall National Museum in Nice (on permanent loan from the Musée National d'Art Moderne), that were cut up from a single work, Revolution (1937-1943). Their iconography has already been researched, notably by Franz Meyer in the early 1960s for his book "Marc Chagall" (Paris, Flammarion, 1964) and Sylvie Forestier in 1990 ("Au cœur d’un chef d’œuvre: Résistance, Résurrection, Libération de Marc Chagall", Rennes, Éditions Ouest-France). This article aims at investigating the history of the three paintings and their journey between France and the United States in the light of new material from the Marc and Ida Chagall Archives.

Revolution

Chagall began Revolution (whose dimensions vary between 168 x 309 cm1 and 167.64 x 307.34 cm2) in 1937 and cut it up into three pieces in 1943, when he started reworking each fragment separately.3 In Meyer’s iconographic analysis, politics plays a key role in understanding Revolution. “The interpretation of the work,” he wrote, “must start with the opposition between its two halves, i.e. between the political revolution and the human and artistic revolution that the painter wants to proclaim.4 Before being cut up, Revolution was exhibited in Belgium in 1938, France in 1940 and the United States in 1942.

Painting and exhibiting Revolution

Brussels, 1938

Correspondence between Chagall and Robert Giron5, head of exhibitions at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, reveals that Revolution was on display there from January 22 to February 13, 1938 under the title The Revolution, in a show devoted to the painter featuring 62 of his works dating from 1930 to 1937.6

The succinct correspondence between the two men highlights how much this monumental work mattered to Giron who wrote to the artist: "I was particularly glad to see that The Revolution is on your list and that this all-important painting will be in the exhibition.”7In a January 8, 1938 letter, Chagall advised Giron on how to hang the painting, and the latter replied: "I will keep in mind the details you have given me about The Revolution and how it should be displayed.”8 These elements provide information on how Revolution was created. On December 15, 1937, Chagall did mention it in a letter in which he explained that it would be displayed in Brussels as soon as it was finished, thus suggesting that it was still unfinished at the time:

“I am working now on the painting Revolution (you saw the little study); the director of the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels saw it and asked for this painting too (when it is ready), along with the others for my exhibition they are organizing on 15/1 in Brussels.”9

In the Brussels exhibition catalogue, Revolution is numbered 40 and dated 1937. It is not reproduced and the dimensions are missing. Little information survives about how the work was critically received. No trace of it has been found in the newspaper clippings in the Marc and Ida Chagall Archives.

Meyer discussed Revolution in his 1964 book. "In 1940, [Chagall] considered the painting finished, but then he destroyed it.”10 The author identified 1943 as the year it was cut up into three parts.11 This confirms that Revolution was not completed until 1940, which means it was exhibited in Brussels in its original condition. As no visual record of the show exists, it is difficult to assess the state of Revolution in 1938.

Paris, 1940. Exhibition at the M.A.I. Gallery

The exhibition at the M.A.I. Gallery on 12 rue Bonaparte in Paris from January 26 to February 26, 1940 featured 30 works, including 11 oil paintings and four drawings. According to the catalogue, the rest of it were gouaches, pastels, oil-pastels and gouache-pastels, made at a later date, with most of them dating from 1938 and 1939. In her 1990 book, Forestier wrote: “When Yvonne Zervos opened the M.A.I. Gallery in 1940, she exhibited [Revolution] under the non-descriptive title Composition. The change of title is indicative of the threats that were beginning to weigh on its author.”12 In her 2020 essay “Chagall, Zervos and Cahiers d'Art”, Chara Kolokytha explained the 1940 show’s specificity:

“Chagall collaborated one last time with the Zervoses before fleeing France. The 1940 Chagall exhibition at the MAI Gallery was a huge success. According to Yvonne's notebooks, nearly 700 people attended the opening, despite the fact that this was quite a chaotic period in Parisian artistic life. Among other works, it presented his 'anti-war' painting Revolution and his famous White Crucifixion, which underscored Jesus's Jewish identity by drawing a parallel between his death and the persecution of the Jews during that period.”13

The Yvonne Zervos papers at the Centre Pompidou’s Bibliothèque Kandinsky14contain no information on the display, no list of works and no visual record of the exhibition. According to Franz Meyer, Revolution was shown in a hidden room at the M.A.I. Gallery open to only a few people:

“It was not until January 1940 that Chagall brought various paintings back to Paris for an exhibition of oils and gouaches organized by Yvonne Zervos to mark the opening of the M.A.I. Gallery. The huge painting The Revolution was hung in a back room under the neutral title Composition, like a clandestine manifesto against war.”15

A painting titled “Composition (oil)”, measuring 309 x 168 cm, and dated 1937-38, is listed as no. 2 in the exhibition catalogue. Research in the Marc and Ida Chagall Archives reveals that on January 17, 1940, Chagall invited Alexandre Benois to the M.A.I. Gallery, emphasizing that Revolution would be exhibited among his new paintings.16 The work is mentioned under this title in a letter from Chagall. Benois did indeed go to the M.A.I. Gallery, since Cahiers d'Art published his article on the show, written in Russian and translated into French, in issue 1-2 of 1940.17 However, he made no mention of Revolution (exhibited under the title Composition).18 Nor did any of the contemporary newspaper articles about the exhibition: If Revolution had been on display to the public, it would not have gone unnoticed by the authorities. The work that drew the most attention from the audience was White Crucifixion (at the Art Institute of Chicago since 1946), shown under the title Christ, which had an impressive size (154.6 × 140 cm) and compelling subject matter.19

Given the political nature of Revolution/Composition, which was exhibited in wartime Paris, the decision to show it only to a restricted circle of Chagall's close friends, such as Benois, also explains why the newspapers did not mention it. Even under the title Composition, Revolution does not appear in any of the press clippings consulted.

Revolution and its three paintings

The Pierre Matisse Gallery, 1942

Chagall and his wife Bella (1895-1944) arrived in the United States on June 21, 194120 joined later by their daughter Ida (1916-1994). A few months afterward, from November 25 to December 13, 1941, the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York held a major “Retrospective Exhibition of Paintings and Gouachesfrom 1910 to 1941”21, initiating the beginning of a close, productive relationship between Chagall and the art dealer. The exhibition catalogue provides information on the 13 oil paintings and seven gouaches that were on display. However, there is no mention of Revolution.

It was in 1942 that the uncut painting was seen probably for the first and last time at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, in the exhibition “Marc Chagall, Paintings, Gouaches” (October 13 to November 7, 1942), as “no. 1, Revolution, 66 x 121 in., oil, 1937-41.”22 There were three works Chagall painted in France between 1937 and 1941, and 13 gouaches, most of them made before his arrival in the United States and three painted in Connecticut.23To date, no press clippings mentioning Revolution at the 1942 Pierre Matisse Gallery exhibition have been found in the Marc and Ida Chagall Archives.

Yet, the painting was displayed there. On November 7, 1942, Chagall wrote a letter to Morgn Frayhayt, a Yiddish Communist newspaper in New York edited by Pesach Novik (1891-1989), responding to an article about the Pierre Matisse Gallery exhibition that gave Revolution a positive review24:

“Thank you for your response to my picture Revolution, which I made almost for the 25th anniversary of the Soviet Revolution. I have never been cut off from the land of my birth. For my art cannot live without it and cannot assimilate in any other country. And now that Paris – the capital of the visual arts, where all artists of the world used to go – is dead, I often ask myself: where am I? I send my sincere greetings and wishes to my great Soviet friends and colleagues – writers and artists, and the even greater artists – the heroes of the Red Army on all fronts. I hope, and I am sure, they will paint with their blood the best and most beautiful ‘picture’ of life’s revolution, which we, simple artists and people, should observe and admire and in whose light we should live.”25

There is another clue indicating that Revolution was known in the United States. In a New Yorker review of Chagall’s 1946 MoMA show, Robert M. Coates recalled the monumental work and expressed his disappointment that it was left out. About the selection of paintings chosen to represent the artist’s 1930s period, he wrote: “But [the exhibition] also omits a number of ‘unsalable’ untypical pieces from the same epoch, notably his big Revolution.”26

This excerpt is insufficient to support the hypothesis that Revolution was still whole in 1946, especially since neither it nor Resistance, Resurrection or Liberation were exhibited at the 1946 MoMA show. The retrospective focused more on the supposedly dreamy or folkloric iconography of his paintings, which overshadowed the political aspect of his work while shaping a sanitized and poetic image of Chagall’s art in the United States. A case in point is the choice of a consensual painting, I and the Village, dated 1911, to illustrate the MoMA exhibition catalog’s cover.

On the other hand, one may assume Coates had the chance to see Revolution at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in 1942 and that it left such a strong impression on him that he expressed regret about its being left out of the painter's first major museum retrospective in the United States.

In “Resistance, Resurrection, Liberation. Chagall's American Masterpiece”, a 2006 essay for the exhibition catalogue Chagall, Exile in America and the Aleko, Benjamin Harshav wrote that Revolution was shown in 1942, but he made a mistake: "At the first Chagall exhibition in New York, a painting called The Revolution(1937-1941) was prominently displayed.”27 The 1942 show was the second time the Pierre Matisse Gallery featured Chagall's work. The first was in 1941. Slightly more importantly, Harshav mistakenly believed that Revolution, presented at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in 1942, was actually a sketch related to the persecution of Jews in Europe at the time:

"Such was the context of Chagall’s ambitious oil painting The Revolution (1937-1941), which was intended as a blueprint for a major mural. Yet there was no patron to pay for such a mural. Five years later, in October 1942, the sketch The Revolution was a centerpiece in the Chagall exhibition in the Pierre Matisse Gallery in October-November 1942 in New York (he apparently finished it toward that exhibition). Yet, there was no interest in the Communist Revolution in America, even though the Soviet Union was an American ally."28

Harshav’s assertion that the Revolution shown by Matisse in 1942 was a "blueprint for a major mural" can be refuted, since the dimensions given in the 1942 Pierre Matisse Gallery exhibition catalogue leave no room for doubt: this is indeed Revolution, which was later cut up. He put forward no evidence to support the hypothesis that Revolution was a project for a mural. The idea of a large decorative work comes up only in a June 1, 1948 letter from Virginia Haggard, the artist's companion at the time, to Ida Chagall, as they planned their return to France:

"It is possible that Madame Anshen will try to find murals for your father, something that is becoming an obsession with him. He is so eager to cover big walls. He has just finished the three pieces cut from the large Revolution. They are wonderful.”29

This is one of the first times the three paintings cut from Revolution are mentioned, but they were not titled Resistance, Resurrection and Liberation yet. In any case, there is no other mention of a hypothetical large decorative project in any of the material consulted. To the best of our knowledge, nothing suggests that Revolution was a project for a mural.

To stick to the facts, the Pierre Matisse catalogues reveal that Revolution was last exhibited in 1942 at the gallery, and that the three paintings nowadays known as Resistance, Resurrection and Liberation were exhibited for the first time in 1948.

Based on current research, we can assume that Revolution was cut up between 1942 and 1948, without being able to specify the exact year.30

To date, nothing in the artist's documentation or archives suggests that Chagall began all three paintings at once. He undoubtedly went back and forth many times between Resistance and Resurrection, which work together. However, the artist had no comprehensive vision for the paintings, which evolved with the historical events happening while he was painting them. They were conceived as independent and complementary works.

The three paintings: Resistance, Resurrection, Liberation

By cross-referencing different sources, it can be surmised that Chagall made the three paintings between August 1948, when he left his High Falls studio to return to France, and November 1948, when the Pierre Matisse Gallery exhibition opened. Haggard’s June 1, 1948 letter attests that he had already cut up Revolution into three paintings before the November 1948 show. Their titles were then Hatikva (often misspelled by Matisse as “Natikva”), Resistance and Ghetto. On September 30, 1948, Bernard J. Reis, a patron of the arts and collector whom Chagall met in New York, drew up a list of works at the Pierre Matisse Gallery allowing the three paintings to be identified. On March 24, 1949, Ida annotated the list for the works shipped to France in June 1950. Here is how they appear in the archive:

Matisse Number Description Chagall Number Size Price in dollars

1859 Natikva 307 100 5,228

1906 Resistance 318 100 5,228

1907 Ghetto 319 100 5,228

The same information is found on a document by Catherine Viviano of the Pierre Matisse Gallery dated October 11, 1948, with Matisse and Chagall’s same notation system: "Dear Mr. Chagall, We received the following paintings from you in June and August 1948”31:

307 C-1859 Natikva (panel) oil 100 5,228

318 C-1906 Resistance (panel) oil 100 5,228

319 C-1907 Ghetto (panel) oil 100 5,228

So the three paintings were at the Matisse Gallery in June or August 1948. On August 17, 1948, Chagall and Haggard sailed to France and settled in Orgeval. The three paintings remained in New York and only returned to France in 1950 as part of a large group of other Chagall works shipped by his daughter Ida. Back in France in August 1948, Chagall sent Matisse a letter in September in which he discussed an upcoming show at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in November and shared his concerns about the three paintings

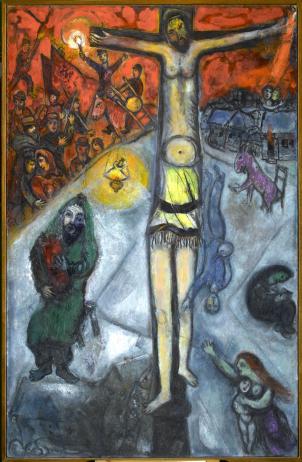

“Virginia wrote to you. I write badly, but nevertheless, I must send you a few words because I feel that you are going to do my exhibition and I am worried as always. I know how magnificent you organize exhibitions and I know your love. I am thinking of that big painting, the Crucifixion (in red) of the series of the three big paintings. I feel that I must rework it – I am not happy with it. But the other two (the sun and the white crucifixion) are better.”32

The letter provides a sense of Chagall’s deep regret at not having the three paintings with him in France to rework them. He wrote of his dissatisfaction with “the Crucifixion (in red)”, which can be identified as Resistance. Based on formal color descriptions, the hypothesis can also be put forward that “the sun” could be Liberation and “the white crucifixion” Resurrection.

The November 1948 exhibition at the Pierre Matisse Gallery

In the catalogue for the Chagall exhibition at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York from November 2 to 27, 1948, the three paintings cut from the Revolution canvas appear under the following numbers and titles:

- 6. Natikva [sic]. 66 x 34 ¼

- 7. Ghetto. 66 x 40 ½

- 8. Crucifixion. 66 x 42 ½

The dimensions of numbers 7 and 8 were probably mixed up or changed at a later date. We propose associating them with these contemporary titles:

- "6. Natikva [sic]. 66 x 34 ¼" : Liberation

- "7. Ghetto. 66 x 40 ½" : Resurrection

- "8. Crucifixion. 66 x 42 ½" : Résistance

To date, no visuals or photographs of the 1948 show have been found. The identification of the three paintings based on the letters sent by Matisse to Chagall in November 1948. In one of them, the art dealer responded to Chagall's intention to sell “two panels” to the Tel Aviv Museum and donate the third:

"I could not hang the three panels together because the red one didn't balance very well with the yellow one, with the crucifixion in the middle, but the whole is very beautiful ... Stern told me about the plan to sell the two panels to the Tel Aviv Museum and your desire to donate the third. The project seems a bit muddled because several people want to get involved. But from several quarters, especially Mr. Lewishon [sic]33 I have heard that the people in Tel Aviv, who are Orthodox Jews, would not like to see a painting like this enter the museum. They are particularly unhappy with the Crucifixions, and I do not know what can be done about that from my end. You should receive $5,228 for every year after our contract. If you donate one, the total would be $10,456. For my part, I must have a commission of at least 20%. Stern would like to know what you could offer as a special price, as you promised. Could you please respond to me about this?”34

In the same letter, Pierre Matisse wrote, “having misread the title of Hatikva, there is an error in the catalogue that I regret very much, but we are doing everything necessary to correct it.”35

There was indeed a typographical error in the title Haktiva (misspelled Natikva in the catalog) and the three paintings were not hung side by side in the 1948 show. It is not possible to identify which two paintings would have been sold to the Tel Aviv Museum and which one would have been donated. Pierre Matisse did not want to see the project materialize. He warned Chagall that the crucifixions would be a touchy issue for a Jewish Museum, but his main concerns seemed to be the loss of commercial control and the awareness that he alone would no longer be responsible for all the negotiations concerning Chagall’s work. Seeing his power crumble, he reminded Chagall of his contractual obligations towards the gallery. In a letter dated November 15, 1948, he wrote:

"I would like to discuss the three panels that you have dedicated to Israel with you. Several people, including Lewishorn [sic], who are Jews if not Orthodox, or at least are aware of the rigors of the Jewish religion, have told me that these paintings could never be accepted in Tel Aviv because Crucifixions would shock the religious groups there. I have made inquiries about this and the opinion is unanimous. On the other hand, a trustee of the museum at Smith College in Northampton likes the painting very much and wants to know if you would agree to sell it, given the unlikelihood that the Tel Aviv Museum will accept the paintings and the fact that you have not finished the red one yet. I would agree to try to get the painting (the one called Hatikva) into the Northampton museum. Given the overall situation, it would be a shame to let an opportunity like this slip away. Three paintings were already reserved, but the sales have been cancelled due to the Hishorn sale, and we do not know how long the crisis will last. So I am asking you, my dear Marc, to make a decision and cable me as soon as possible so that we can strike while the iron is hot. The situation is quite serious, and it is best not to go off on a wild goose chase pursuing some project whose uncertain outcome depends mainly on public funding, since the money for the two panels must be found, which at the moment cannot be taken for granted. Think it over carefully and cable me as soon as possible. All of 57th Street has the jitters. Business has come to a complete standstill.”36

In the context of postwar economic austerity, Matisse came up with an alternative to Chagall's initial plan: selling the paintings to the museum in Northampton (they never were). When he wrote, “the fact that you have not finished the red one yet”, he was undoubtedly referring to the letter from Orgeval (quoted above) in which Chagall shared his doubts about the painting (possibly Resistance). It is important to note that Matisse chose the words “panels dedicated to Israel”. The same wording is found in a letter that Chagall wrote in Yiddish to poet Abraham Sutzkever at the end of 1948 in which he expressed how delighted he was to learn about the creation of the magazine Di Goldene Keyt:

“I am glad that a Yiddish journal will be published in Israel. Thank you for inviting me to participate. Very happily ... In the meantime, I am sending you a poem (written by chance in Russian on my first visit to Paris after the war – 1946. I cannot find my Yiddish translation, but I think you can do it better). I am also sending you a picture of the 1948 series dedicated to Israel: 1) Ghetto; 2) Resistance; 3) HaTikva. I am sending you the third one. I think you should print the picture as a frontispiece, i. e., the whole page preceding the text of the journal – as was once done in the Zamlbiker collections, edited by Opatoshy and Leyvik, or in another one of his [Opatoshu’s] books. I shall enjoy reading your journal and wish you all the best happiness.”37

In the same letter, Chagall wrote the words “series dedicated to Israel” and suggested that Hatikva be reproduced in Di Goldene Keyt, which it was.3

In a letter to Chagall dated January 6, 1949, American collector Louis E. Stern shared his concern about Pierre Matisse's nervousness and suspected a private or professional reason. He called the group of three paintings seen in November 1948 a “triptych”: “It is for that reason I did not get any information on the results of the recent Chagall exhibition. As for myself I found the triptych quite exciting. Did Pierre mention anything to you about the three large pictures?”39 Perhaps Stern knew about Chagall's plan to have the three paintings exhibited in the Tel Aviv Museum and was asking about their fate. This is the first time the word “triptych” appears in correspondence about the paintings that Chagall and Pierre Matisse called a “series dedicated to Israel”.

None of the three paintings was sold or donated during Chagall's lifetime. They remained in his possession until his death in 1985. In 1989, Resistance, Liberation and Resurrection joined the national collections of the Musée d'Art Moderne in lieu of payment of inheritance taxes. Since 1990, they have been on permanent loan to the Marc Chagall National Museum (formerly the Musée National du Message Biblique Marc Chagall) in Nice.

Reception in the press

A few press clippings provide sources for studying the reception of the November 1948 show at the Pierre Matisse Gallery. Crucifixion, Ghetto and Hatikva drew the attention of several journalists, especially since they were the largest formats in the exhibition among the 11 other oil paintings and six gouaches on display. Some writers mentioning the works reproduced Pierre Matisse's typographical error in the exhibition catalog, where Hatikva was misspelled Natikva. A black and white photo of Hatikva reproduced in an article by Emily Genauer in the New York World Telegram shows the painting in its early state. After the 1948 Pierre Matisse Gallery exhibition, Chagall continued to rework it until 1952.

Crucifixion, Ghetto and Hatikva were not hung side by side but as stand-alone paintings, creating connections with the other works on display through their common subject matter, as Robert M. Coates wrote in The New Yorker:

"There are some new subjects, notably a big Crucifixion in which the Christ figure is portrayed against a rather symbolic Russian setting, the whole suffused with red, and a less successful Ghetto. All the others, though – Bride with Flowers, the blue Flying Fish, the more vigorous, slightly enigmatic Double Portrait and Natikva[sic] – run close to form, and it’s amazing how really lovely most of them are."40

Hatikva seems to stand apart in its formal treatment, colors and subject matter. It looks brighter than the other two, with the couple hugging in the lower right-hand side. Coates dissociated the crucifixions in Ghetto and Crucifixion from Hatikva, which he compared for instance to Flying Fish (1948), whose subject is much less oppressive.

A New York Herald Tribune critic also paired the two paintings with a religious subject, without referring to the third panel Hatikva:

"While Chagall reaches out continually toward new goals, as in the Ghetto and Crucifixion drawing upon themes of sublime tragedy, he is never quite so successful with them as with pictures that betray the simpler emotions.”41

An Art News journalist noted that the crucifixions (Resurrection and Resistance) were the most notable among the other works on display:

"Most are pretty and may perhaps best be characterized by the term ‘schmalz’. Exceptions must be made, however, for two little blue panels of the painter at work, two large Crucifixions and a Double Portrait. Here sharp, abstract designs give interest and strength to the usually soft forms, yielding a precise mixture of poetry and fantasy."42

The review was accompanied by a black-and-white reproduction of Crucifixion (see below) that shows the first state of the painting, which Chagall reworked subsequent to returning to France after 1948. In the final painting, Chagall added an upside-down blue figure on the right side of the crucified Christ. A row of blue-roofed houses has replaced the man with the ladder in the upper-right background and, after 1948, the man with the upside-down stool under the donkey seated to the right of Christ on the Cross became a man with a green face reading. The composition changed less on the left side of the painting, but a man with a candlestick under the cross was erased, and a fish appears in the final painting. This refers to Christian iconography and migration, to crossing troubled waters. The photo, published in Art News, is an invaluable source for studying Chagall's work and allows a better understanding of how the painting was created.

In Orgeval, Chagall also reworked the other two paintings, especially Liberation, which features the most conspicuous changes. The alterations can be checked visually from the photos reproduced below. The first shows the state of Liberation in 1948 reproduced in Isaac Kloomock's book. The second is a 1952 picture of the finished work in its final state as we know it today, on loan at the Marc Chagall National Museum in Nice. The differences outlined by Meyer in his 1964 monograph can be identified: "In 1948, Liberation was already signed and dated. A subsequent reworking, which removed some figures and intensified the color, lasted until 1952.”43 For example, the roof of the house was replaced by the color yellow, which floods the space and brightens up the whole composition.

The evolution of the three titles

The history of the titles can be traced by researching the catalogues of exhibitions in which the paintings had been shown since November 1948 at the Pierre Matisse Gallery. In Franz Meyer's illustrated catalogue Chagall, published in French in 1964 (Flammarion), they have their definitive titles: Resistance (no. 829), Resurrection(no. 830) and Liberation (no. 831).

The “blue” painting displayed by Pierre Matisse in November 1948 with the title Crucifixion was called Resistance at the 1953 Turin exhibition, the first time it was shown in Europe. The “red” painting he exhibited as Ghetto at Pierre Matisse’s was later renamed Resurrection. After 1948, the only time it was shown under the title Ghetto and it was first exhibited in France in 1959 as Blue Crucifixion, a name kept until 1964.

Liberation was first exhibited by Pierre Matisse in November 1948 as Hatikva, then reproduced in black and white in Isaac Kloomok's book Marc Chagall: His Life and Work (New York, Philisophical Library, 1951) with the title Hatikva (Dedicated to Israel). Hatikva means “hope” in Hebrew and is the title of the national anthem Israel adopted at its creation in 1948. Chagall's painting was called Liberation in 1951, when it was included in the travelling exhibition “Marc Chagall. Works, 1908-1951" in Israel.

The idea of a triptych

Interestingly, the three works were seldom exhibited together in the postwar years. As seen earlier in the correspondence between the art dealer and artist, the paintings were not hung side-by-side at the November 1948 show.

They first appeared together in a 1964 exhibition on Metz stained glass at the Musée des Beaux-arts in Rouen under the titles Resistance, Liberation and Crucifixion in Blue (today Resurrection) but were not referred to as a triptych. Then the paintings were displayed separately until 1991, when they came together as a “triptych” at the “Chagall en nuestro siglo” exhibition in Mexico City. They have been inseparable ever since.

The very concept of a triptych is not obvious in the case of the three works created by cutting up Revolution. In his 1964 monograph, Meyer called them a "triptych”44 and "panels”,45 but also "fragments”.46 He also used the expression “stand-alone compositions”:

“Another large prewar painting, Revolution from 1937, combines images from Chagall's earlier works with others based on alarming current events (pl. p. 392). It was a monumental composition that he later reworked and eventually cut up in 1943. Two of the three parts, which became stand-alone compositions, received new titles reflecting contemporary political events: Liberation (cat. ill. 832) and Resistance (cat. ill. 830).”47

In the 1988 documents leaving the paintings to the French State in lieu of inheritance taxes, while each has its own inventory number, the estate value applies to all three together. The numbers are "HT 1060 Resistance, 1948 / HT 1061 Resurrection, 1948-52 / HT 1062 Liberation, 1952.”48 It was probably from this point on that the paintings were considered a whole. The term “triptych” has been systematically used since 1990, when, in her book Au coeur d'un chef d'œuvre Résistance, Résurrection, Libération de Marc Chagall, Forestier wrote that, in her personal and formal interpretation, they can be considered as such. While Forestier was not the first to use the word in reference to the paintings but she theorized about it and justified this choice at length, referring to its religious connotations. She emptied the iconography of its political content to give it a much more spiritual tone, a perspective taken up in exhibition catalogues since 1990.

On the other hand, in 1964 Franz Meyer interpreted the paintings through the lens of the political events Chagall lived through,49 an interpretation borne out today by studying correspondence, press clippings and exhibition catalogues. This in-depth research led to a reassessment of Chagall's link with politics in the 2023-2024 travelling exhibition “Chagall politique, le cri de liberté” at the Musée de la Piscine in Roubaix, the Fundación MAPFRE in Madrid and the Musée National Marc Chagall in Nice.